The relationship between cinema and politics, in conventional and superficial understanding, manifests as cinema that overtly asserts a political stance or functions as political propaganda. However, the dynamic, subjective and malleable nature of this relationship is evident in the rigorous debates it has provoked. Political cinema extends beyond the conventional to refer to the portrayal of socio-political realities and histories.

Cinema and politics are loaded terms that contain the possibility of multiple meanings, functions, and interpretations. Cinema, for instance, is a form of entertainment media, artistic expression, and mass media. Politics, similarly, is not merely a reference to the affairs of the state, but also deals with the relationship between citizens and the state.

Source- Wikimedia

Turning our gaze inwards towards India, Bengali cinema serves as a prototype for understanding this kind of political cinema. When I refer to Bengali cinema in this case, I am referring to the ‘triumvirate’ that is Satyajit Ray, Mrinal Sen, and Ritwik Ghatak. They experimented with various film techniques and aesthetics and strived to mirror and often critique the political, social, economic, and cultural ambiguities of their time.

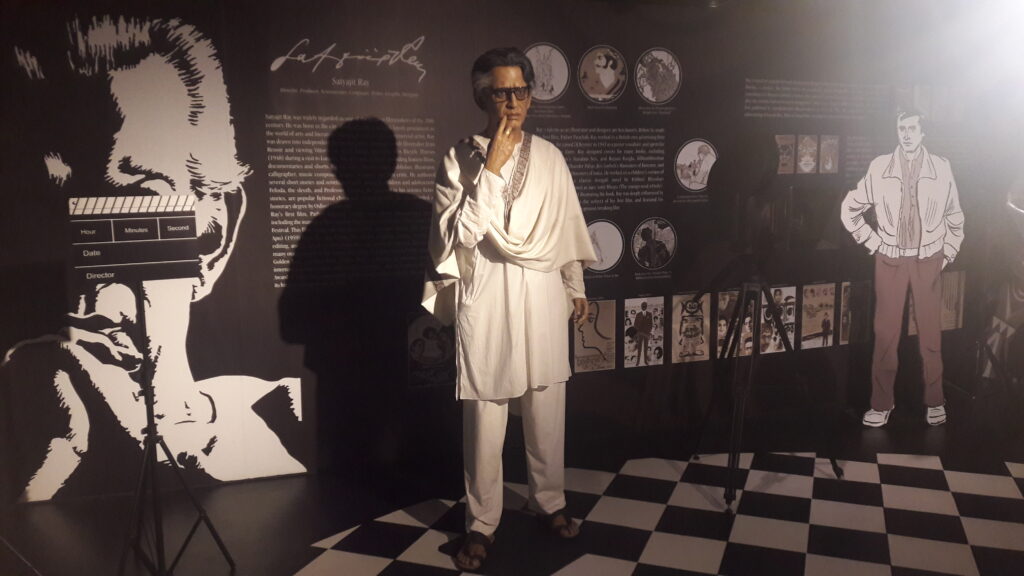

Satyajit Ray’s films are best known for their visceral character. While Ray’s filmmaking abilities and aesthetics have been acclaimed, he has been critiqued as being a romantic who had abandoned his critical role as an artist. His works, hence have often been relegated as apolitical, neutral commentaries rooted in humanistic, bourgeois liberal values. However, there are others like Chandak Sengoopta, a professor in the department of history at the University of London who contest this view. In his article titled ‘The Cinema of Satyajit Ray: In the Prison-house of Humanism’, he asserts that Ray did in fact adopt a strong ideological political viewpoint in his films, that of “modernist, cosmopolitan liberalism” with a belief in Nehruvian ideology and nationalism. However, this ideological stance underwent a transition that can be traced through Ray’s filmmaking career.

His famous Apu trilogy, filmed in the early phase of his career, consisting of Pather Panchali(1955), Aparajito(1956), and Apur Sansar(1959) narrates the life of a lower-class protagonist – Apu- and his encounters with the life of the rich. According to Sengoopta, Ray’s depiction of Apu’s life trajectory mirrored Nehru’s vision of a “progressive, nationalistic narrative for India” in which the problems of the time would be resolved through a rational and secular approach. This approach is also evident in his film Jalsagar (1958), – a portrayal of the inevitable decline of the feudal zamindari system and the triumph of the modern bourgeois lifestyle. Jalsagar has also been interpreted as a critique of modernization and consequently the replacement of feudal society and traditional values with capitalistic corporate values.

Source- Wikimedia

It is in Ray’s Calcutta Trilogy, comprising Pratidwandi (1970), Seemabaddha (1971), and Jana Aranya (1975), that we see a shift from this ideology. This change runs parallel with the declining enthusiasm of Nehruvian politics in the face of increased corruption, unemployment, and oppression. Pratidwandi depicts the sharp ideological conflicts between two brothers, one a Marxist-Leninist-Maoist, and the other an individualist dreamer. The stereotypical depiction of the former and the focus on the latter is testimony to Ray’s own strong beliefs in individual freedom. This, he expressed himself in an interview published in the ‘Cineaste’ titled ‘The Politics of Humanism’. The same has also been noted by Amaresh Misra in his paper titled ‘Satyajit Ray’s Films: Precarious Social-Individual Balance’. He asserts that the characters in Ray’s films, while representing the socio-political realities of their time, also appear as individual autonomous beings.

Hemango Biswas with Ritwik Ghatak

Source- Wikimedia

Jana Aranya (The Middleman), on the other hand, is a critique and depiction of the all-pervasive unemployment, corruption, and political upheaval in Bengal in the 70s.

In the same interview in Cineaste, Ray also remarks on the use of fiction and fantasy as efficient tools of political commentary. He refers to a scene in Hirak Rajar Deshe(Kingdom of Diamonds)(1980) in which many poor people are driven away and claims that this was a reference to what happened in Delhi and other cities during the Emergency period. Sengoopta notes that this film also alludes to the fluid boundary between totalitarianism and liberalism.

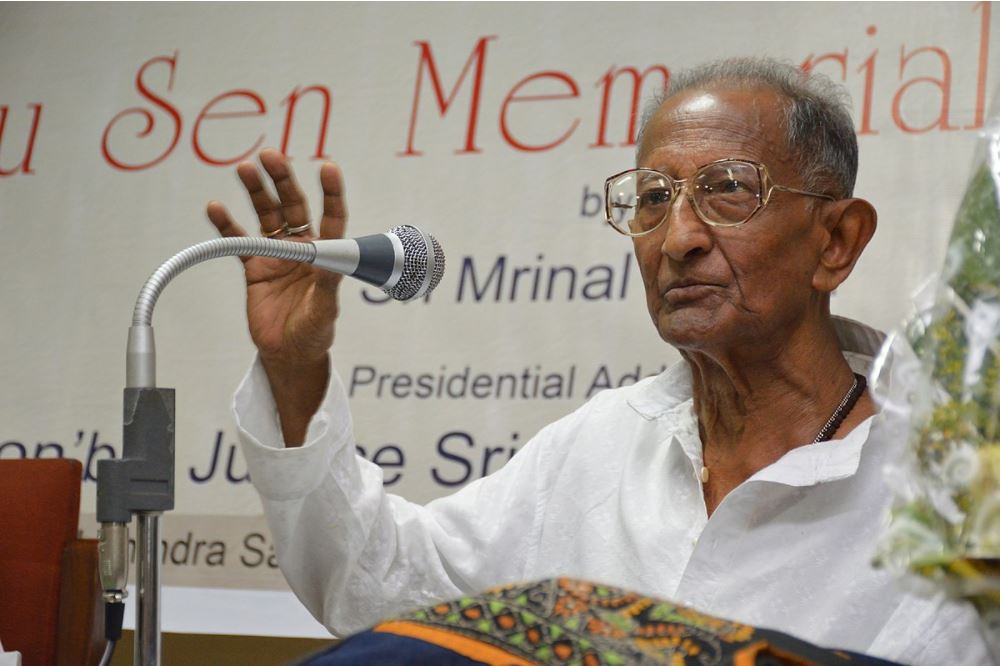

Unlike Satyajit Ray, Mrinal Sen’s films are considered to be overtly political. Through his films, he sought to create a politically conscious and sensitive environment conducive to debate. For Sen, the fact that his films were provoking individuals to levy harsh criticism was testimony to their effectiveness. (Jump Cut, no. 12-13, 1976, pp. 9-10). Sen also clarifies the difference between making films politically and making political films. By this, he alludes to the ambiguous nature of politics and claims that situations or events that might not deal with something conventionally political, can be portrayed in a manner that invokes political sensitivities.

Sen’s films portrayed his own Marxist ideals. However, his evolution as a filmmaker is accompanied by his evolution as a thinker as well; he discovered certain gaps in these Marxist ideals and began to critique them in his films. His film Padatik(1973) – part of his Calcutta trilogy which also includes Interview (1970) and Calcutta 71(1971) – is a reflection of this critique. Padatik, which depicts the decline of the Naxalite movement, was Sen’s plea for self-criticism in the face of the predicament of the leftist movement.

Source- Wikimedia

Calcutta 71, a compilation of four short stories, deals with the themes of poverty, starvation, and oppression. On the making of Calcutta 71, Sen comments –

“I wanted to interpret the restlessness, the turbulence of the period that is 1971, and what it is due to. I wanted to have a genesis. The anger has not suddenly fallen out of anywhere. It must have a beginning and an end. I wanted to try to find this genesis and in the process redefine our history. And in my mind, this is extremely political.” (Jump Cut, no. 12-13, 1976, pp. 9-10)

This trilogy dealt with various issues of poverty, famine, and unemployment in a harsh and bold manner. Such a depiction is in contrast with the more romanticized version of poverty presented in the films of Ray. For Mrinal Sen, poverty was the result of exploitation by the system, not just an inevitable condition of human suffering.

The outspokenness of Sen’s films has been aptly noted by the film critic Derek Malcolm, who claims – “All Sen’s films, even his most lightweight, have attacked with undisguised horror and anger the poverty, exploitation and inherent hypocrisy of Indian society.” (Sight and Sound 50, no 4 (1981), p 262)

While Mrinal Sen acquired widespread recognition for his work, Ritwik Ghatak’s films, which are a reflection of his own life history and experiences, did not gain popularity during his lifetime. He used his films to explore the tragedy of the Partition of India in 1947. However, instead of a violent depiction of the same, he focused on the upending of the social, gender, and caste relations that ensued. As observed by Swagata Chakravorty in her article ‘Out of the Waiting Room of History: Ritwik Ghatak’s Cinema of Partition’, Ghatak deals with the political ambiguities that arise from a violent displacement of individuals and their “loss of subjecthood”. His famous partition trilogy of Meghe Dhaka Tara (The Cloud-capped Star) (1960), Komal Gandhar (E Flat),(1961), and Subarnarekha (The Golden Thread)(1965) showcased individuals grappling with these struggles.

Source- Wikimedia

Komal Gandhar deals with the aftermath of the violent partition and the divided leadership of the Indian People’s Theatre Association (IPTA) – the artistic and cultural organ of the Communist Party of India of which Ghatak was a part. The film led to a controversy that forced Ghatak to look for work outside Bengal for a while.

Megha Dhaka Tara, based on the novel by Shaktipada Raj Guru, is a representation of how Ghatak used metaphors and melodrama to produce an engaging film that deals with the survival efforts of a refugee family. The protagonist of the movie is considered by many theorists and critics to be a metaphor for newly divided India.

Subarnarekha, which is the last film in the trilogy, deals with the refugee crisis and issues of gender relations, caste, and even morality. The protagonist of the film seems to be a spokesperson for the plight of women in post-colonial India as she struggles to balance the loss of identity as a refugee and her prescribed social role as a woman.

These filmmakers, due to the style and content of their films, are considered to be the pioneers of the New Wave Cinema movement which emerged in West Bengal in the 1950s. Ray’s work with its humanitarian, lyrical, and yet political character; Sen’s evocative and unflinching critique of the politics of his time; and Ghatak’s experimental narration techniques coupled with his use of metaphors and the portrayal of human suffering as a result of state politics bestowed a new dimension to the political cinema of India, one that was also celebrated internationally. While their work has influenced many, the revolutionary character of their films remains unparalleled.

Being an art and culture enthusiast, Sumira is an avid reader, a passionate dancer and a curious writer. She has a keen desire to learn and feels strongly about the issues of diversity and inclusivity. She finds solace in food, music and the company of her friends.

Thank you for sharing superb informations. Your website is so cool. I’m impressed by the details that you have on this site. It reveals how nicely you understand this subject. Bookmarked this website page, will come back for extra articles. You, my pal, ROCK! I found just the info I already searched everywhere and simply could not come across. What an ideal web site.