Socio-cultural milieu across the globe have almost always been identified by particular cultural hallmarks of which its folk traditions are most discernible. The Indian subcontinent, too, nurtures innumerable forms of artistic expression through folk theatre, songs, art, etc. One such form is the bidesiya, exclusive to the ‘Bhojpuri speaking belt’ comprising parts of Bihar and Uttar Pradesh. Unlike most other folk genres, bidesiya, usually has no explicit religious, mythical, philosophical underpinnings but is a product of historical changes and cultural interactions that define the period of British colonialism in India.

The style derives its name from the eponymous drama Bidesiya, by Bhikhari Thakur, a Bhojpuri poet, playwright, performer who rightly received the appellation ‘Shakespeare of Bhojpuri’. The episodes of the play are a scathing attack on the British regulated system of labour (coolie, girmitiya) migration to man and reinforce the burgeoning industries in India and abroad and the socio-cultural ramifications of the same. The protagonist, a young man in search of employment owing to the distressed economic conditions with the fall of indigenous industries, absence of agricultural land, decides to leave behind his aurat (spouse) in the village and relocates to Calcutta, which was then a hub of English enterprises, thriving on imported labour.

The play’s success leads to the production of songs, plays with similar titles and contexts but altered with geographical and cultural nuances. Although set in a similar blueprint, the lyrics accommodated changing historical realities of caste, juxtaposition of gender identities, reorientation of human relationships, material markers of ‘modernity’ like railways, etc. Most notable here is that the expression of a majority of the song/ play is from the perspective and voice of a woman who tries to get her grievances redressed by venting her anguish and longing for her beloved.

The changing material conditions of life are exceptionally well entrenched in the songs that abundantly engage with revolutionary markers like the introduction of railways, as noticed in words from a very popular song ‘Reliya Na Bairee’–

The railway has become a co-wife,

It has taken away my beloved.

Instances of songs on the journey of the Bidesiya migrant back to his town was an instance of doubled pleasure as the novelties of city and English tastes like clocks, boots, bicycles, etc that men brought with them were a source to instilled awe among the rural folk, which also gave the women the opportunity to brag about the luxuries and thus move up the social ladder.

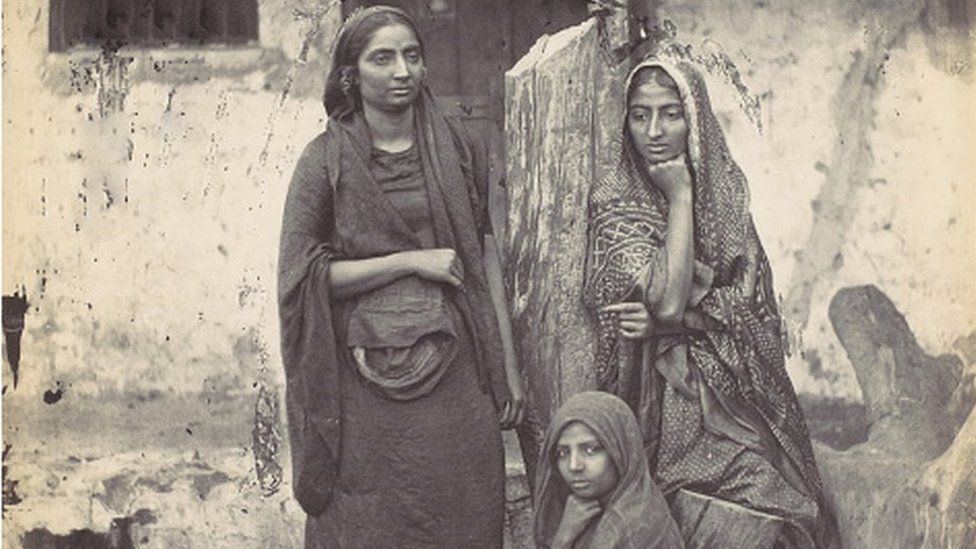

Photo: Chris Walker Collection/The Restoration & Archiving Trust ©

The songs most importantly manifest the social realities and familial environment that the ‘wife’ has been left in by the husband. They reflect the callous treatment meted out to her, who has neither borne a male child yet nor was able to bring good luck to the family, which forced the son to wander around in search of livelihood. She is scorned at for being financially dependent on in-laws and thus, out of a decision taken about her life, constant attention has been drawn towards the woman who, in the face of a debauched environment, resists all sorts of temptations and dutifully awaits the return of the bidesiya [the foreign husband and the protagonist] without giving in to any enticement that might bring her chastity into question. The glorified image of a woman who lived up to the ideals of submission, devotion and unconditional love for her man has been highlighted.

Through the paranoia of the wife about the dalliances of the migrant labourer, which turned out to be true in most cases, these pieces highlight the moral depravity that crept into city life and corrupted those who came in association with it. Performances represented how men at some point became so indulgent in cohabiting with other women that they forgot altogether about their wives in the villages who, irrespective of being aware of their men’s illicit affairs, never harboured the desire to separate from them.

The theatrical performances till today are performed by men only wherein the launda (female impersonators) play the female protagonists as transvestites even though a substantial part of the audience comprises women, at least in the present decades. The flexibility of the genre makes it an important instrument to showcase social ills and anomalies and devise ways to correct them, as seen in Bhikhari Thakur’s play where the mistress, her children and the wife ‘share’ their husband without animosity and live-in harmony.

© https://www.patnabeats.com/bidesia-dance-the-heritage-of-folk-dance-in-bihar/

The peculiarity lies in the perpetuation of the songs/plays till today due to its mass popularity and wider reach of theatrical performances as channels to disseminate awareness on contemporary social evils like female infanticide, dowry debts, etc. Of the very few folk traditions that have historical foundations, bidesiya is important because it keeps alive the trajectory of the Bhojpuri belt as sources of labour to inland areas and abroad till date.

Most of the popular compositions carry a social message and is a reminder of a convoluted past that stemmed from a terrific civilisational confrontation. Irrespective of the immense contribution to the theatre world, the genre has a limited audience primarily due to the distorted political ambitions of the nation’s stakeholders, which has further dwindled with the onslaught of the pandemic. They’re living on the edge due to strained economic circumstances. Thus, our moral responsibility as members of a civil society is to help ensure a decent life for these artists by accepting and promoting such art forms that personify our historical richness.

From Dhanbad, a history graduate from LSR. Currently a first year Masters student in Delhi University. I religiously experiment with cuisines! I spend my free time drooling over fictional characters and listening to music. Personally follow and urge everyone to follow the 'live and let live' principle in life. Current Role: interning with ITISARAS as a writer. Ultimate goal: To help create consciousness about animal-welfare and be of help in the strive for universal education. Biggest achievement: helping an adolescent with no educational background learn the basics of language, to read and write. Educational Qualification: History graduate, currently a Masters student at Delhi University.