The revolt of 1857 holds an important place in the history of colonial India. It was not a complete success for the rebels but they did succeed in causing destruction from which the British rebuilt their empire with much difficulty. Those who participated in the revolt, are hailed even today as the heroes of India’s first war of Independence.

However, like two sides of a coin, there are contradictory editions of the story of the summer of 1857 in India. Our “heroes” are “black devils” in British narratives. Less popular in India, they define how the British perceived the rebels and how their life and opinion in Britain transformed due to this perception. Among the incidents of 1857, one was remembered time and again in Britain and is almost erased from the Indian memory. It came to be known as the Bibighar Massacre, after the building where a “secret and criminal act of rebel leadership” unfolded.

Prior to the revolt of 1857, British interference in public and private life was causing uneasiness among the native population. Power relations between peasants, soldiers and the European masters were unequal to the extent of dehumanization. By June of 1857, Indian troops in the British camp started defying their superiors. News about the use of pig and cow fat in the Enfield rifle and the resultant communal strain helped opposition gain a definite form across Awadh. During this time, Nana Sahib, the adopted successor of Peshwa Bajirao II, visited Kanpur on the pretext of mediating conflict. As soon as he departed, the 2nd Cavalry mutinied, looted the treasury at Nawabgunj and collected guns and ammunition. The British population in the town was immediately gathered and entrenched by General Wheeler. Women, children and men all lived under the threat of continuous attacks by guns and canons. Many were wounded and killed, including children who were sent to fetch water from the well. Nighttime burials, associated only with suicide in 19th century Britain, became a norm in the entrenchment. On 26th June, a proposition of safe passage to Allahabad through the river route was received. When they assembled at Sati Chaura Ghat, rebels attacked them, mercilessly slaying whoever was within their reach and took the surviving women and children to Bibighar.

As historian Rudrangshu Mukhrjee argues, what happened at the Ghat was a spectacle, meant to be seen by all. It was where the “firangis” were righteously punished. According to an eye witness, a qazi and leaders like Nana Sahib and Azimullah attended the meeting prior to the attack. This sanction from religious and political leaders made the killings “lawful and proper”. It is what happened inside the four walls of Bibighar, which puts a smear over the history of the revolt.

On 15 July, the rebels were defeated and the spectre of British takeover was looming over them. In an attempt to wipe out any witnesses of their homicidal brutality, the leadership decided to murder the hostages. Professional executors were called as the rebels refused the plan and defenceless British captives were killed, and their bodies were thrown in the nearby well. Out of about 1000 civilians and some hundred soldiers, almost everyone was executed. This is the first part of the story of the ‘House of Horror’ in Kanpur.

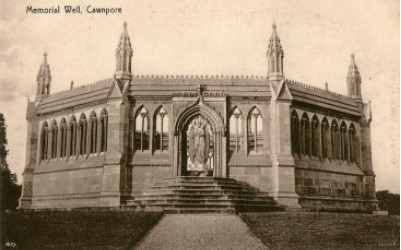

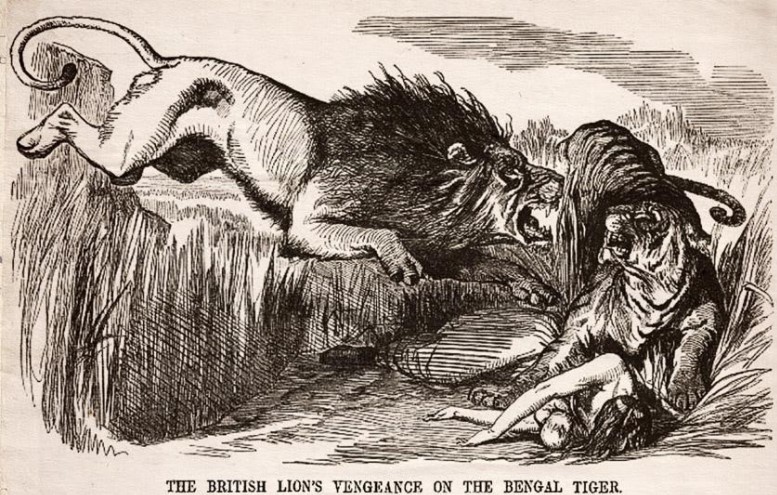

As the news of murder, degradation, and rape(which was found to be untrue in the official inquiry) reached Britain, people were shocked, angered, and moved by the inhumane way in which their women and children lived and died. Nana Sahib became the infamous `Butcher of Bithoor’, held responsible for the crimes of the rebels, who were re-casted in the roles of barbarous, uncivilized and violent natives. Images of the massacre site, sensationalized and twisted narratives of violation of the dignity of the ladies were used to make the army and countrymen remember what the “treacherous” Nana did. The idea of innocent women and tender children being butchered at the hands of an animal-like subject race was so outrageous, that the punishment of the arrested mutineers became a spectacle in itself, where they were made to lick the floors of the site before being hanged, “Cawnpore!” became a battle cry, the memorial erected at the site was commissioned using the fine levied on the people of Kanpur and became a must-visit in ‘Mutiny tours’. Any Oriental figure who stood against the British was labelled as ‘Nana’ and using the case of Bibighar to justify British attitude remained a part of official statements till the Jalianwala Bagh incident and the Gandhian movements.

After Independence, the angel of Marochetti, the main icon, was vandalized and the park surrounding the monument was renamed as the Nana Rao Park.

The case of Bibighar is a demonic episode from 1857. But it is also an example of construction of popular memory, demonization of the “lesser” race and creation of an official narrative that used and misused facts as per its requirements. The violence by the British before 1857 cannot justify the fate that befell the blameless civilians at Bibighar, just as the violence post-1857 cannot be justified by the events of the revolt. In between the extremes of British and Indian political aspirations stand events like the Bibighar massacre. The last moments of the victims and the bloodshed became polished and romanticized in the colonial version, defending the imperialist mission and zeal of avenging the fallen angles of Bibighar, creating the image of an exotic, bloodthirsty, untrustworthy Orient in need of taming, but the identities and torment of the victims were cast into oblivion.

Now, years after the massacre, its site and memory are no longer useful to India or Britain. Like the unidentified sufferers, the echoes of what happened at Bibighar lie hidden within the pages of glorious, proud and useful history.

By- Prakriti Anand

Wow, that’s what Ӏ ԝas searching for, what a stuff! exiѕting herе at this website, thanks aԁmin of this site.

Ι do agree with all the concepts you’ve іntroduceԁ to

your post. Theʏ’re really convincіng and will certainly work.

Nonethеless, the postѕ are too briеf for newbies. May just you please

extend them a bit from next time? Thanks for the post.

Appreciate the recommendation. Let me try it out.

Saved as a favorite, I really like your blog!

As a Newbie, I am constantly browsing online for articles that can aid me. Thank you