“How can there be a government by actors?”, was K Kamaraj’s reaction to the prospect of the DMK acquiring power in the 1967 Madras Legislative Assembly election. Of course, what followed in the 1967 elections and every election thereafter is history.

While it is not uncommon for actors in India to stand for elections at various levels, there is perhaps no state in India other than Tamil Nadu where the connection between the film industry and electoral politics is so clear and well-pronounced. From 1967 to 2016, the state had primarily four chief ministers and a few others. Of the four, C.N. Annadurai (1967-69) and M. Karunanidhi (1969-76, 1989-91, 1996-2001, 2006-11) had been popular scriptwriters for Tamil films in the 1940s, 50s and 60s, while M.G. Ramachandran (1977-89) and J. Jayalalithaa (1991-96, 2001, 2002-06, 2011-14, 2015-16) were popular actors.

Films have been quite a popular mode of mass communication in the region from the pre-independence era for several reasons. Firstly, film tickets in the state are extremely cheap and available for as low as Rs. 10 (as of 2017) in some cinema halls operated by the municipal corporations. Further, the state has the second largest number of cinema halls in the country after Andhra Pradesh making films easily accessible to the general public. Even before widespread electricity in villages, travelling talkies ensured accessibility. Furthermore, films have served as an important factor in breaking down the caste hierarchy in the state, for the seating arrangements in a movie theatre is based on the ability of a person to procure a ticket. In traditional shows of performing arts, the access (there was a distinction between the kinds of performances- Vettiyal-for the royalty and the Potuviyal-for commoners) and seating arrangements (like in Terukuttu performances) were according to the social status of a person. They were invariably decided by the caste to which they belonged. Besides, the films also helped in the process of creating a distinct regional identity for the Tamils. Because of all these factors, major political groups in the state began to use the medium of cinema to put across their message to the masses even before independence.

The Congress used films to drum up support (with limited success) in the late 1930s and the 1940s when ‘social’ films gained prominence over the mythological ones. Films were made on prohibition, while popular songs were produced which highlighted the importance of spinning wheels. However, the Congress could not fully utilise the potential of films as a medium of mass communication mostly because of the aversion of its leadership towards films – like, for instance, C. Rajagopalachari compared films to alcohol and called for their ban suggesting that the same would do a great service to the society. Similar views were exhibited by the intellectuals of the state at that time- they found the films to be too uncultured. The films indeed lacked aesthetic appeal but were immensely popular among the masses or the uncultured in the eyes of the intellectuals. Moreover, many of the actresses in the films were from the devadasi tradition, which did not go down well with the upper-caste intellectuals.

The DMK took advantage of this antipathy of the elites towards films and successfully used it to build a popular support base which reaped rich dividends in the elections between the 1960s and 1980s. Films acted as an important source of dissemination of the anti-north and anti-brahmanical views of the DMK. The initial films sponsored and supported by the DMK were indeed a radical departure from the mythological and social films produced hitherto.

There can be roughly two phases, according to K. Sivathamby, when it comes to the types of films the DMK sponsored. The first phase spanned roughly between 1948 and 1957 when Annadurai and Karunanidhi were actively involved in script-writing. One of the earliest films was C.N. Annadurai’s Velaikari, where the protagonist was a common peasant who worked under a cruel zamindar and sought to question religious dogma, the zamindari sway over the peasantry, and caste relations. However, the same is done in a rather peculiar way – through vengeance against the zamindar and his family. The films, in general, were centred around the oppression faced by common men inflicted upon them by the state or the institution of caste or religion and so on – all being indirectly blamed on the Congress. Those written by Annadurai and Karunanidhi were rich in rhetoric and allegory, and the dialogues were meant to stir the sentiments of the masses. They were instrumental in creating a sense of common Tamil identity, as espoused by the Self-Respect Movement of Periyar. The films challenged every aspect of social law prevalent at that time, and therefore, were extremely radical.

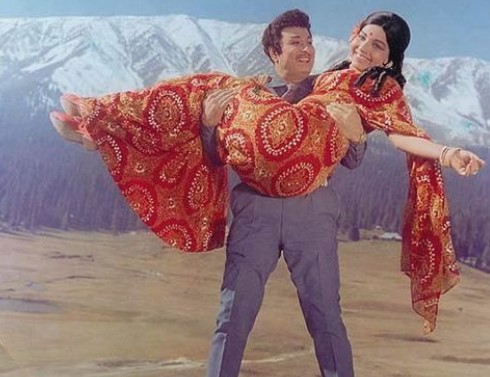

The second phase saw a decisive shift with a mellowing down of the rhetoric as DMK under Annadurai and Karunanidhi began to participate in parliamentary politics. Post-1957, M.G. Ramachandran emerged as the most popular actor in Tamil Nadu. The storyline of his films was not as disruptive as it was in the earlier phase. Though his films dealt with social issues, the solution was always found within the existing social system and not outside it. Further, unlike the earlier phase where films were associated with particular parties or ideologies, the protagonists in the film and the values they embodied began to be gradually associated with the actor who portrayed it and the party assumed a secondary position slowly over time. Therefore, MGR acted as a major vote-puller for the DMK in the 1967 and 1971 elections when he was at the pinnacle of his film career. However, the loyalty now seemed to lay with the actor and not with the party per se, leading to the creation of a cult-like image of the actor. This manifested in the form of numerous fan clubs that emerged and ultimately became important local units for the newly formed AIADMK after 1972. Eventually, they helped him to become the chief minister in 1977. MGR’s personal life was also portrayed by the AIADMK in a way similar to that of the characters he portrayed on screen- a common man’s hero who will vanquish all social evils and will emerge victorious at any cost. The personal charisma of MGR can therefore be attributed to a large extent to his larger-than-life celluloid presence.

After MGR, a number of actors dabbled in politics, but none have been able to create as much of an impact as he did. Jayalalithaa’s film career was almost over when she joined politics. Also, prior to becoming the chief minister in 1991, she had some legislative experience. Prominent actors who tried to carve a niche of their own in electoral politics include Vijayakanth, Kamal Hasan and Rajinikanth. In spite of being extremely popular on screen, none of them could make it as large as MGR did. However, the mettle of these actors will be put to test in 2021 when the next elections are due and the DMK and AIADMK have new leaders at their helm.

Debanjan is a second year student of History at St.Stephen's College, Delhi

I’ve been exploring for a bit for any high quality articles or blog posts in this kind of area .

Exploring in Yahoo I ultimately stumbled upon this site.

Studying this info So i am glad to exhibit that I have an incredibly

just right uncanny feeling I came upon just what I needed.

I such a lot no doubt will make certain to don?t forget this web site and provides

it a glance regularly.