Languages, and by extension, texts that are written in these languages in the Indian subcontinent have often been associated with particular religious communities from the 19th century, as similar sentiments began to be reflected in the colonial and the nationalist histories of the 19th and 20th centuries. As a result, the medieval texts within the Indo-Persian traditions with a Muslim ‘hero’ have been broadly categorised as the “Muslim epics of conquest,” while those composed within the Sanskritic traditions centred around a Hindu ‘protagonist’ have been classified as “Hindu counter-epics of resistance.”

However, certain literary genres, like the premakhyans were difficult to classify under these broad categories, because of their rather complex form emanating from an amalgamation of various literary traditions in the subcontinent. The premakhyans were composed only for a limited time period from the late 14th century to the mid-16th century and specifically by Sufi poets patronised by the local hinterland courts (not the central court based in Delhi). Composed in Hindavi, these versified romances had significant Sufi overtones and borrowed extensively from the Persian masnavi tradition, as well as the Sanskrit mahakavya traditions representing a continuity from the existing classical literary traditions. At the same time, their orientation was rather unique and set apart from the classical traditions. It can be considered as a wonderful example of ‘indigenisation’ of classical traditions.

The most important premakhyans in chronological order were- Mulla Daud’s Chandayaan, Narayana Das’s Chitai-Charita, Sheikh Qutban’s Mrigavati, Malik Muhammad Jayasi’s Padmavat and Mir Manjhan Shattari’s Madhumalati. After Madhumalati was composed in the 1540s, there is no surviving evidence of any premakhyan; perhaps because of the consolidation and centralisation of the Mughal polity under Akbar, which led to the decline of the provincial courts. It needs to be pointed out that the hero typically belonged to the class of provincial elites, and one of the hurdles faced by him was often a conflict with the overlord- usually the sultan of Delhi like Alauddin Khilji in Padmavat (possibly) and Chitaicarita and Bahlul Lodi in Mrigavati. While the latter cannot be defeated militarily, the hero vanquishes him through his strength of character, his valour and spiritual pursuits. The martial nature of these texts can be traced to both the Sanskritic and Persian traditions.

Mulla Daud was the pioneer of this genre, and the later poets followed the tradition set forth by him. Though the premakhyans were written in the Persian masnavi format, the narrative style was centred around the aesthetics of the Sanskritic rasa. Rasa, defined by Bharata in the Natyasastra, refers to the ‘juice’ or the ‘flavour’ of the poem arising from the vibhava (source of rasa), anubhava (actions, experience) and vyabhicaribhavas (transitory emotions). As the Rasika (the connoisseur of the rasa), the sahrdaya or a cultivated reader can experience the emotions of the lovers in the poem, and also the poet’s personal feelings and affections. Moreover, the premakhyans make extensive use of symbols and idioms from the mahakavya traditions. For instance, Aditya Behl mentions how the description of the female figures from head to toe in the premakhyans was heavily influenced by the nakh-sikh-varnana in the mahakavya traditions, which had parallels with the sarapa in the masnavis.

The main plot of the premakhyans revolved around a tragic romance between the male and the female protagonists, who battle numerous hurdles during the course of their union. However, the nature of love between the protagonists, as Daud Ali points out, was far more sedate and domestic when compared to the early medieval premgathas, wherein the nature of love depicted was much bolder and more erotic. In a period of great social and political ferment, the premakhyans acted as important didactic texts by embodying ‘ideal’ protagonists.

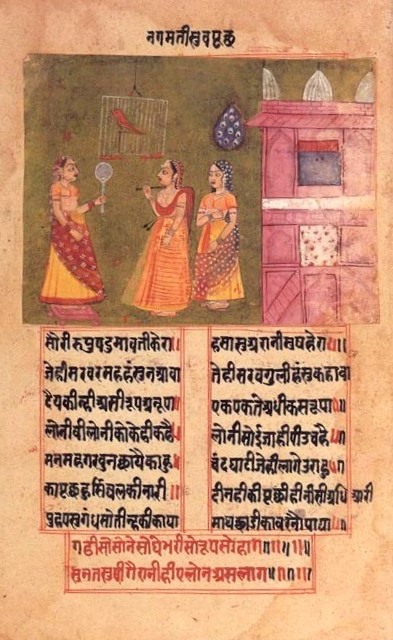

source:wikimedia

As pointed out earlier, these texts were authored by the disciples of Sufi saints, and therefore, these texts were replete with the Sufi symbol and even the main plot surrounding the quest for the beloved can be seen as an allegory for the Sufi quest of the Divine Truth; for fana with the unification of the lovers (even in death) symbolising the unification of the devotee with his God. Throughout the texts, the several hurdles faced by the hero are symbolic of the pervasive worldliness which hinders the unification with the Divine- for instance, in Chandayan and Padmavat, the heroes are torn between two women- representing the material and the spiritual milieus respectively. In cases like Padmavat, the Jauhar becomes the symbol for fana, while the same is represented in the Chitaicharita by the adoption of natha mendicancy by the protagonists, Chanda and Lorik. These texts are replete with misery and sorrow faced by the protagonists, which again becomes an allegory for the arduous journey the disciple embarks upon towards the quest for Truth.

Indeed, the premakhyans were a potpourri of several cultural and textual traditions and were reflective of the churning that characterised the 14th-16th centuries. These texts were meant to be read to the Sufi disciples and were extensively borrowed from existing local traditions by the poets who textualised them using classical literary styles. However, the perception towards these texts was altered significantly by the colonial period when the colonial scholars embarked on a translation spree. The incidents of sacrifice and valour of the ‘Hindu’ protagonist became symbols of nationalistic pride and these tropes were also used by the British to pit the Hindus and Muslims against each other. Time and again historical scholarship has pointed to the fallacy of the views – these texts (particularly Padmavat) have gained considerable attention in recent times, with the revival of the trope of unabashed Islamic tyranny within the mainstream thought process. As a result, these texts have been seen through a communal lens by the wider audience, even though the interaction between the ‘Hindu’ protagonist and the ‘Muslim’ sultan was merely a sub-plot and not the central narrative of these texts. It needs to be remembered that these texts are extremely complex and any study of them needs to be nuanced in nature – for any reductionist approach would rob these texts of the meaning they intend to convey, as has been the case in the contemporary scenario – not only with these texts but with others as well.

Debanjan is a second year student of History at St.Stephen's College, Delhi