Zikr-e-Dilli is a digital repository of material and spatial memories and narratives of the city. It was founded in June 2020 by Anukriti Gupta and Tanuja Bhakuni. Anukriti Gupta is a PhD candidate at the Centre for Women’s Studies at Jawaharlal Nehru University. She holds an M.Phil degree in Women’s Studies from JNU, a Master’s Degree in Gender Studies from Ambedkar University, Delhi and a Bachelor’s Degree in English Literature from Lady Shri Ram College. Her research interests include gender, space, faith practices, material culture and public history.

Tanuja Bhakuni is a doctoral candidate at the Centre for Women’s Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University in Delhi. She did her graduation in Political Science from Lady Shri Ram College and has a Masters in Gender Studies from Ambedkar University. Her research interests include visual culture, history, cityscape and city spaces, region, public and identity.

Kunal Chauhan: What inspired you to open Zikr-e-Dilli, and precisely, what inspired your particular brand of history writing which involved a very personal and cultural, yet factual approach?

Anukriti: We started Zikr-e-Dilli in June 2020. Tanuja and I both study at the Centre for Women’s Studies, JNU and have been discussing our experiences, memories and ideas around the city for the last 2-3 years. We always wanted to start something like Zikr-e-Dilli, not necessarily on Instagram initially, but we chose Instagram so that we could reach out to more and more people through social media. We basically wanted to look at different histories, different memories and lived experiences of people around the city of Delhi. If we talk about the triggers, why we chose something like this

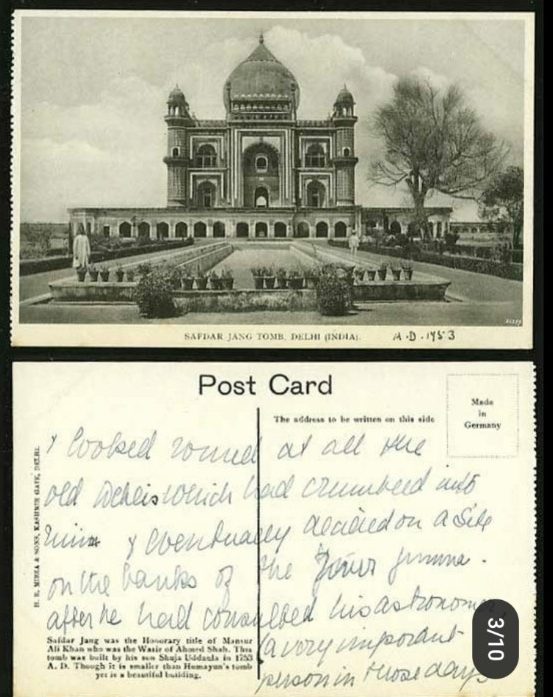

— we were noticing that in contemporary times, in Delhi, or in any other city for that matter there are very clear, neat binaries. For example, this part is “Old Delhi” and this is “New Delhi”, this is “anti-national”, this is “national”. We wanted to look at the engagements between different categories and not keep anything in one box – how do we talk about different memories, experiences of people through histories, literature, letters, postcards and such. You would have noticed that we experiment with many different forms in our posts. So the idea was how can we bring all of that together.

Tanuja: I think the journeys both of us have been through are quite similar. So Anukriti is from Patna and came to Delhi around 10 years ago. Similarly, I was born and brought up in Delhi NCR- I live in Noida, but my first instance of experiencing the city as an individual was after I came for my bachelors to LSR. So that was the first time I was travelling to Delhi on my own and experiencing it as a woman travelling on her own and seeing places. It’s quite interesting – both of us met in LSR, but we were in different courses and then we pursued masters in gender studies, but I completed it in 2014, whereas Anukriti took admission in 2014. Finally, we met again in JNU, so it kind of came as a full circle for both of us. The city and the spaces have made us what we are and having similar experiences motivated us into taking up this experiment, I think.

Kunal: I think that’s very interesting. As you mentioned, Anukriti is from Patna originally, and Tanuja you were born and brought up in and around the Delhi NCR region, so both of you had very different experiences growing up in very different areas. So what particularly about Delhi’s spaces inspired you to write about it? A lot of your posts are also about the personal histories of people from Delhi. Is this fascination with personal history a function of your academic background, or is it personally determined?

Anukriti: I think it’s both. If we talk about our personal experiences, we have been moving around in different spaces of Delhi for the last 10-11 years. From South Delhi to North to Old to South-West Delhi. There is no one experience – the spaces are so contingent that the different spaces of Delhi evoke very different memories. From love to critique to hate, there are very different opinions. In 2018 and 2019 we used to talk about the videos coming up on social media titled “South Delhi Girl” or “North Delhi Girl” which depicted very fixed, homogeneous identities. Like “this is what a South Delhi person looks like, or speaks like” or “this is how someone from Old Delhi behaves.” Both of us used to talk about how the Delhi we have seen in the last 10 years is quite different – there are many ‘Delhis,’ not one. In one of our first posts, we talk about many gates of Delhi. There are so many gates to enter Delhi, and everyone with their given background enters and sees Delhi very differently. Regardless of whether the person is living in South Delhi, or North Delhi, how can we homogenise their experiences?

So, it has a lot to do with our personal experiences in Delhi and also relates to our academic backgrounds. Our research is very multi-disciplinary, and hence we have been looking at our research areas through many lenses. So drawing from that, how do we look at city space through many categories? This has also influenced our posts.

Tanuja: I think Anukriti covered most of what I wanted to say. As she said, it was driven by our own experiences – both personal and professional. Academically, we work with a multidisciplinary approach, where we are looking at different things through different lenses such as gender, space, identities. I think that was another point that came into our writings because those are the different categories through which we have been engaging in our research work. So that flowed very organically into our posts as well. We did not think we are writing ‘history’ particularly, but rather, the approach was to look at the history very differently and not just in the mainstream sense of “history writing”, but through memories, through space, maps, objects. That was the idea.

Anukriti: I recently mentioned in one of the posts, if a person goes to visit any popular monument – say, Taj Mahal, if you ask a person about their experience, he may not necessarily tell you the history of the place but will talk about his own memories. What did he feel when he first saw that space, what did he notice, who was with him, from where did he go to see the Taj Mahal? In their personal narratives, people build stories around these monuments very differently– not necessarily through historical details but through their own memories and backgrounds. We have been trying to do this in most of our posts – how do we touch this personal way of looking at historical spaces or other public spaces in Delhi.

Kunal: The urban history of Delhi has been very much centred around select spaces and themes, for example on the Sultanate or the Mughals. With this background, how is your page influencing public perception around the urban history of Delhi?

Anukriti: So when we say urban history, first let’s look at how people are building their histories around the urban spaces. For example, if we are talking about New Delhi, urban spaces which came up in the last 50-60 years, or post-independence in New Delhi – can we easily and very neatly separate them from historical, older spaces of old Delhi? We cannot. One good example is Ambedkar University. So Tanuja and I were discussing this for the last few days. Tanuja, if you would like to continue –

Tanuja: Yeah, so we have been thinking about putting up a post like this for a long time. Both of us were part of Ambedkar University, and although I had some idea about the Kashmiri gate and it is a part of the Mughal legacy, especially during the 1857 uprisings and everything, I was not very familiar with the spatial history of it. So when I came to Ambedkar University, I think it was the first time I was seeing the building and I saw the Dara Shikoh library there. We were there for two years and we saw this space and Dara Shikoh in a very different way. Even though this space has a long history, and during British times it was a part of the Delhi College, for us it was a very different kind of space. So Anukriti and I were just talking about how one should understand this monument not only as a monument but also as an everyday space for students, teachers and others. How do they perceive the monument? It’s not very distant to them and is personal – this also flows into the history of the monument. These spaces and their histories are transforming constantly through people. I think this was something we were thinking around – how do we look at these monuments – can we still call it a monument? How does it change with these times within the campus?

Anukriti: If we see Ambedkar University as a modern university and that space as an urban space then how can we talk about the presence of Dara Shikoh library in the middle of that structure? And not just Dara Shikoh library – there are so many monuments around Ambedkar University – St. James Church, Kashmiri Gate -located at just a 3-minute walking distance from there. So you see how there are layers of multiple histories in many urban spaces of Delhi. So how can you neatly separate the urban from the historical? When you talk about Ambedkar University and its modern education in that space inhabited by so many students from all over Delhi, you need to talk about the historical part of it as well. What does it mean to study in that space which once belonged to Mughals and then to the British? There are many spaces like Ambedkar University in Delhi – so how can you conceptualise the idea of urban or historical, or Old Delhi and New Delhi? So that’s what we have been emphasising – that it is very difficult to homogenise all these spaces of Delhi.

Tanuja: Similarly, I was thinking of another example on which of our posts was based. It was around the Tughlaq play that took place in Purana Qila. It was a very modern play in a sense – though it was talking about the Emperor, it is actually taking place in the ruins of the Purana Qila. So how do we understand this kind of conceptualisation – it’s a play from post-modern times and written from the context of the Nehruvian era. How does the monument play into this history? So these were some of the anecdotes we were thinking around – the idea of a ‘living museum’ is something Anukriti and I had been discussing. These are certain things that come to our mind.

Kunal– I think it’s so interesting that you mentioned Ambedkar University since my next question is in connection to the same. So your account was one of the first to historicise the colleges of Delhi. How do you think these college spaces are important in history as social and cultural spaces?

Anukriti: So I think one of our first posts on college histories – was titled “Girls from LSR, JNU, Miranda House Need Not Apply.” I think it went viral in one or two hours and thousands of people liked it. And Scroll, ScoopWhoop, the Print – many news portals shared that article and wrote about it. This triggered a debate about women’s colleges in Delhi. This was a very popular phrase when we were studying in LSR, and then JNU. This was the perception around women’s students – not only in Delhi but also outside. When I was coming to study in Delhi from Patna, some of my extended relatives were very particular that I should go to LSR but not study at Stephen’s. Since LSR is a women’s college, they said “don’t apply in a co-ed college”. Even with women’s colleges, there were so many comments about how Delhi is not a safe place and women from these colleges learn so many things when they go to Delhi, they become “over-independent” and that this kind of independence is “not good for our family.” There were a lot of such narratives about women’s spaces in Delhi. Then we posted about this, but at the centre of the post were the histories of women’s colleges. But people related to the title and liked those pictures, as many people from DU follow our page. But the main point the post was trying to make was that Delhi has a very long history of women’s colleges, and how these women’s spaces have developed over time. These spaces are not perfect and have their own limitations and we did mention this in the post – but I think the caption got a lot more attention than the content of this post. We have been a part of three very different universities – JNU, Ambedkar University and Delhi University. So, many of those posts are somehow coming from our own experiences.

Tanuja: Actually when Anukriti was writing this post, she was doubting it and asked me whether we should post it or not. We were thinking of writing the history of women’s institutions in Delhi, and it was coming from a very personal experience of occupying these spaces. I think because both of us are from LSR, and it was quite a common quote or phrase that was being tossed around and we used to laugh about it and think about it, we thought it would be interesting to start the post with that line. Ultimately it was actually talking about these spaces and was very much embedded in our own experiences of occupying those spaces. We were trying to locate the histories of those spaces.

Kunal: So as you just mentioned, you deal with a lot of personal histories and the modern cultural past of Delhi, in this context what is your approach to the sources? Which piece or theme from your account has been the most difficult to source?

Anukriti: We have been thinking about this because we write a lot about personal history, but we have been entering the domain of personal history mostly through literature, theatre, films, historical anecdotes, letters and also through our own personal experiences. Something we have been discussing for a long time is how we can include the personal experiences of other people of Delhi. Perhaps starting with people of our own colleges, or other colleges at Delhi – looking at the youth first and then maybe including other people. We have been thinking of how to go about including these other narratives and personal experiences. We will be launching our website soon – in March – and we are adding a new section to Zikr-e-Dilli, which is called the ‘Living Museum of Delhi’. In this, we are starting with spatial and material memories and we will be requesting people to contribute their memories with photographs or in a written form around spaces of Delhi, and materials. For instance, in one of the posts, I wrote about library cards of LSR college, and how my library card and College ID became the first tangible sources to relate me to Delhi. When I first came to Delhi I was about 16-17 years old, and that was the first tangible sense of feeling related to this place, this very new city I knew nothing about. We are sure there must be many such memories that people must have around Delhi and its spaces – in their college years, or when they started working. Especially memories around spaces – say, public transport or monuments or the place where they first lived, their college hostels. So we will be doing that soon – where we include other people’s voices and stories or critiques they have to tell around Delhi. This is something we have been feeling for a long time – how do we write not just through literature? Even though we find many interesting anecdotes from literature – for example, we have written a lot about the streets of Delhi. If you see Ghalib’s and Mir’s couplets, they valourise the streets of Delhi – how once you enter Delhi, you can’t leave its streets. But when Amrita Pritam is writing about her character Kamini in ‘Dilli ki Galiyan’, and how she enters the city through its galis, Kamini continuously talks of how she feels very insecure on the streets. There is a sense of disenchantment with the spaces of Delhi, and she wants to leave the city as soon as possible. So these are very different approaches towards the streets of Delhi, or towards its public spaces. We have been trying to cover these things through secondary sources so far and our personal experiences, but now we will be adding more voices to Zikr-e-Dilli.

Tanuja: Since we are not looking at Delhi through one particular lens, it also gives us an opportunity to explore different types of sources. We try to get as creative as possible with our sources. I think that is something we always try to do – we’ve looked at films, theatre, transportation, music, poetry, personal visits, art, artists. We try to be a little creative so that we don’t get stuck in our sources.

Anukriti: Most of the time we try to add a historical background. Our posts are also very factual. Even when we are entering memory and personal anecdotes, we always try to contextualise it historically.

Tanuja: The sources are not just personally driven, in that sense – we always try to locate the personal in the social and political. Even if we are writing our own experiences, we mention the time period and what is going on. I think that is very important to give the person a very seated approach.

Kunal: It’s very interesting to hear about your upcoming projects, and with the website coming in and the narratives you will put forth, I am so excited as an avid reader of your Instagram page so far. I am truly looking forward to a full website where there will be a lot more content. Now coming to my last question – given that Anukriti, you’ve been in Delhi for 10 years, and Tanuja you’ve been exploring it much closer in the past 10 years, how would you describe the spirit of Delhi very briefly?

Anukriti: So with respect to the spirit of Delhi, since we have not homogenised any space or history of Delhi in our posts- and we are engaging with all these spaces, categories and histories of Delhi with a very multi-disciplinary approach- so I can’t pinpoint any one attribute which represents Delhi. For example, there are so many layers of history and how we see Delhi or how we imagine Delhi- it’s continuously changing. Not just the critical main moments like 1857, Independence- not just those- but even today. So for example, if we talk about the space around Red Fort- how it gained newer meanings after January 26th, 2021. In the contemporary collective memory around protest sites in Delhi, people think that all these protests are majorly centred around Jantar Mantar and India Gate, and the old Delhi Red Fort Area- it’s not very active in protests. But if we look at that period, it’s not very far from us. Just before the 1970’s or the Independence- New Delhi was not a site of protests, and all the major protests, rallies and baithaks took place in Old Delhi- in the grounds of Red Fort, Parade Ground, Town Hall, near Chandni Chowk- all these areas. And after the Bangladesh War of 1971 when India Gate was announced as the memorial of the unknown soldiers- after that slowly protest sites shifted towards New Delhi.

So if we make contemporary times as our central point of looking at protest sites in Delhi, how can we forget that the areas in Old Delhi have been active in protests? This is not the first time that Red Fort’s space was occupied for protests- those areas have been active. And again when we talk about the spirit of Delhi- do we always only talk about the popular spaces in Old Delhi and the kind of romanticisation that goes around its spaces. So then how can we talk about Karawal Nagar or Seelampur or Okhla or Chattarpur- and so many other localities in Delhi which we never talk about. Those areas have their own histories, experiences, memories. So I think the spirit is too small a word to capture what Delhi is. So the many gates of Delhi that we have been talking about in our posts- there are many Delhis existing parallelly. Sometimes they contradict each other, sometimes they overlap- but they are moving forward together. So the many spirits of Delhi cannot be defined in any one attribute.

Kunal Chauhan: Tanuja if you would like to continue?

Tanuja: I think that is because our understanding of Delhi is constantly being discussed – like she said that for us there are multiple Delhis which have spanned through different times and different spaces also. So I think like what she said that these not even distant but immediate histories are also being omitted and are being seen in a very binary sense- the understanding of history has become very binary in that sense. So I think the idea of this recollection of Delhi- of this living museum- actually attempts to disrupt that idea of a binary in that sense. Again I want to say that through these histories we then attempt to understand this very complex idea of what Delhi constitutes and personally for me, then, I want to look at Delhi in a very hopeful sense through these histories. That is what I would like to end with- it’s very difficult to define for us also since we have experienced Delhi in very different ways. Still, we want to see Delhi as a hopeful space for people who are living here and people who want to come here and experience this space.

Anukriti: And also people who have left Delhi and are still remembering it and continue writing about it.

Tanuja: Yes, still remembering and continuously writing and talking about it. I have friends who have left Delhi for like 10 years and who are still talking about it- if anything happens they immediately call up and ask what’s been happening here and there- so I think that is what we want to capture.

Anukriti: So basically what is our idea of Zikr – because we emphasise that a lot – it means recollection. It’s a continuous process, a continuous effort on remembering, recollecting Delhi and what it is, what it can be and what it was- how can we bring everything together.

Tanuja: Also it’s a very conscious effort on our part in that sense- a very conscious effort on our part of that recollection.

Kunal Chauhan: Yeah I think that is very interesting and it has been absolutely lovely talking to the two of you about so many different aspects of Delhi – the material spaces, the culture and the memory- so many different narratives that are there around the city. Very similar to Tanuja, I was born and raised in Delhi but then again, you start experiencing the city once you get that sense of independence- once you go through school and join college and then you actually start travelling around the city. You are no longer in a very guarded setup and you are actually exploring the city by yourself- there are so many different narratives and perspectives. I really admire the work that you are doing at Zikr-I-Dilli – it’s good to read your posts and regularly follow whatever you all have been doing so far.

Thank you so much for doing this interview and being a part of our ongoing edition of the heritage spaces of Delhi and I wish you all the very best for your upcoming website – I’m very eagerly waiting for your website to go live. On behalf of the entire team of Dhaara, I am very grateful that you agreed to do this – thank you so much!

Anukriti: Thank you!

Tanuja: Thank you so much!

Kunal is a Delhi based lawyer & policy analyst and has been working in the social sector since the last seven years. He is the Founder of ITISARAS and currently presides as the Chairman of the Governing Body of the organisation.