With its impressive history of dynasties and diverse cultures, Delhi is more than just the capital of India. It is symbolic of the rich diversity and fusion of cultures woven into the very fabric of the country. Architecture has been a central characteristic in the city’s display of diversity with monuments and buildings ranging from different eras like the rulers of the Delhi Sultanate, the mighty Mughals, or the Colonial masters dotting the stunning skylines. However, amidst the renewed pride and celebration of culture and nation, what remains conspicuously missing is an ode to the legacy left behind by Nehru and larger concern for the sly attempts being made to overshadow it.

Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru—the first Prime Minister of Independent India—the ‘architect of modern India’ in more ways than one, wasn’t just an exceptional statesman who guided the nation through many challenging times during the infancy of its conception. He was also one of the greatest patrons of art and architecture in India. In the years immediately after Independence when Delhi was ravaged by an influx of refugees, unravelling under the tragedy of Partition and faced with the pressures of ‘catching up to the West’, Nehru had a vision that he sought to bring to life. Architecture, for Nehru, held an important role in building a cultural vision of a new, democratic and egalitarian society and a new citizen, and he sought inspiration from the radical modern movement in Europe with its socialist roots.

Hence the several buildings commissioned in Delhi between the 1950s and 1980s were more than just part of a utilitarian project seeking to fulfill the infrastructural needs of the city within the limited resources of the time. Rather, it was an ambitious mission to reclaim the narrative and build the ethos of a newly democratic and progressive nation seeking to leave its mark on the world. The designs reflected an extremely cosmopolitan and self-assured nation that soon became a source of inspiration to other designers who visited and worked in India. The Nehru enlisted young Indian designers and architects such as Habib Rahman, Achyut Kanvinde, Durga Bajpai, Charles Correa and others in this endeavour to transform the face of the city and bring his vision to life. Initially under the aegis of the Central Public Works Department, buildings like the Supreme Court of India continued to follow the Colonial style mastered by Lutyens and Baker. However, influenced by Le Corbusier and his work in Chandigarh, the Modern architectural style

soon came to be favoured. modernist architecture was a nod to the progressive future that Nehru had envisioned long before India got her freedom.

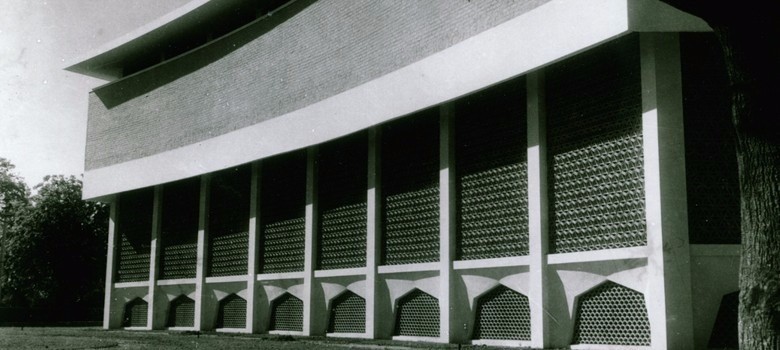

A spate of buildings which neither drew from India’s traditional architecture nor mimicked the West, such as the Rabindra Bhavan (1961), the Indraprastha Bhawan (1965),Shri Ram Centre (1969) and the Vikas Minar (1976) began to mark the skies of the city. Referred to as “Regional Modernism,” these buildings came to be characterised by details such as the use of locally available stone and decorative ceramic tiles. Other landmarks of modern architecture in Delhi include the IIT Delhi (1961) by Jugal Kishore Chodhury, Hall of Nations (1972) and Asian Games Village (1982) by Raj Rewal, Palika Kendra building (1984) by Kuldip Singh, and Lotus Temple (1986) by Fariborhz Sahba.

Today, an attempt is being made to overthrow this remarkable architectural legacy that Nehru had set in stone. It can be viewed as part of a greater political agenda catering to the current regime’s carefully crafted and selectively discriminating narrative. The recent trend of renaming historic landmarks or commissioning works of architecture in a pompous display of power, most notably the new Central Vista, are all part of this attempt at conveniently erasing or distorting a significant part of India’s history that doesn’t align with the Hindutva ideology. The 2017 demolition of the Hall of Nations in the name of adding renovations, demolition of the Nehru pavilion in Pragati Maidan, or the plans to change the nature and character of Nehru Memorial Museum & Library and the Teen Murti complex; despite both National and international condemnation for the same, send across a clear message. The PM and the ruling party have not shied away from expressing their disdain for Nehru, yet to go so far as to undermine his life’s work and destroy invaluable heritage in the process is truly abominable.

The new Central Vista project is then not just a snubbing of our colonial history as the government in power would like to present, but it is the frontrunner in their masterplan to rewrite history as they see fit and present a new face of an Indian civilisation devoid of the diversity of its past and its struggles. The old Central Vista, while a product of Lutyens’ Delhi and not of Nehru’s modernist architecture, is symbolic of the Congress’s struggle to reclaim the national seat and Nehru’s work in establishing Indian Democracy. This tug of war between ideology and politics is manifesting itself quite aptly in the realm of architecture. Delhi has borne witness to

different regimes that have ruled from it’s seat and each regime has set out to cement its mark for eternity by leaving behind a unique architectural legacy, a powerful visual representation of the cultural impact they had on the people of the land. Today, the current regime’s attempt at the same is happening at the expense of the very same architectural legacy of Delhi and it is Nehru’s Modernist architecture that seems to be fading into the ruins.

I’m not sure why but this website is loading extremely

slow for me. Is anyone else having this problem or is it a

problem on my end? I’ll check back later on and see if the problem still exists.