In light of what happened on 26th January 2021 in Delhi, questions were raised on the ongoing farmers’ protest—taking place against three farm acts passed by the Parliament of India in September 2020—on grounds of the movement’s alleged involvement with the secessionist Khalistani agenda. While such allegations can weaken the cause of the protesting farmers, the Indian state cannot remove itself from the danger of such possibilities of secessionist forces making use of the situation to deviate people from a legitimate cause or give it religious overtones.

India has witnessed secessionist tendencies in other regions too, including the Northeast, Kashmir, and some Naxalite-prone areas in central India. As it has been noted, the politics of secession isn’t simply of a region trying to become autonomous for its cultural unity, but involves stakes of multiple parties that are not usually seen on the face of the movement. These parties can include neighbouring countries sharing borders with the region or big business groups that might benefit from the situation economically.

When viewed retrospectively, the Punjab crisis of 1984, which saw the development of the Khalistan movement, provides us with important lessons on the center-state relationship. Political insecurity of parties at both levels, state and center, can lead to the growth of fatal incidents such as what India witnessed during the course of the Khalistan movement.

The root of the Khalistan movement goes back to the era of Partition. Sikh leaders had wanted to create a Sikh state along the lines of Pakistan, however due to lack of political support and Sikh population much less than a Muslim one, there was a reluctant agreement on the division of the Punjab region. This involved the migration of large numbers of Sikhs from the ‘other’ side of the region. The aspirations of a separate state, however, were visible with initiatives such as PEPSU (Patiala and East Punjab States Union), uniting eight princely states between 1948 and 1956, followed by Punjabi Suba Movement, which ultimately resulted in the formation of Punjab state, a movement that was led by the Akali Dal. However, despite being a strong advocate of Sikh culture and religion, the Akali Dal could never gain a full Sikh support in the state’s party politics. The Congress Party remained effective with its widespread support from the Hindus, members of the scheduled caste and the non-scheduled caste rural Sikh population.

Till the 1970s, the Sikhs’ long-held grievance against the federal government had been that while the water from the three rivers, Ravi, Beas, and Sutlej flowed through Punjab, an elaborate canal system diverted the water to drier areas of the states of Rajasthan and Haryana. There were also reservations regarding the official language of people living in Punjab and growing sentiments to protect the Sikh identity within a Hindu majoritarian state. Sikh resentment was also intensified by the regular tussle between the Congress and the Akali Dal in the Punjab region. The growing popularity of Congress among Hindus in Haryana drove the Akali Dal to come up with the Anandpur Sahib Resolution in 1973. Apart from the economic issues in Punjab, demands were also raised to protect the Sikh identity. The resolution was not secessionist in nature but rather, called for greater autonomy for Punjab.

The economic and political crisis began to take religious overtones when parties like Akali Dal started expressing their social demands in the name of religion. This led to a rise in militancy in Punjab. Sikh fundamentalism can be traced back to 1978 when regional leader Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale assumed the role of a religious preacher and figurehead in the Sikh community. The situation was aggravated by members of the Akali Dal and its various splinter groups, as well as internationally among the Sikh diaspora. Within the Sikh diaspora, there were sympathisers of the community living abroad, mostly the US, UK, and Canada, who provided organisational support to the movement. Some sections of the Congress party too instigated this radicalisation to weaken their main parliamentary opposition in the state, the Akali Dal, which had considerable support from the Sikh peasantry.

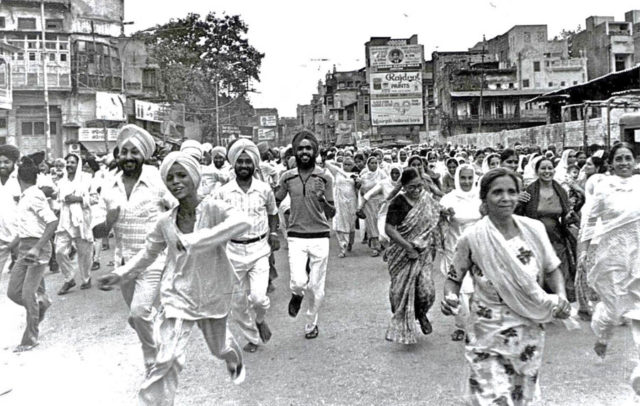

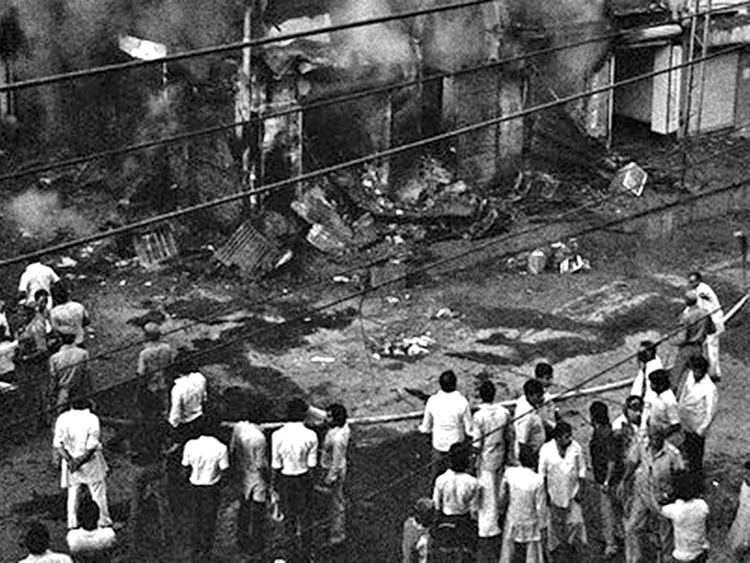

The militants grew and took shelter in the premises of the Golden Temple in Amritsar in 1982. This happened under the leadership of Bhindranwale. He was able to rise to his level as a result of the tussle between the state party and the center. By this time, the movement had become highly violent. President’s rule was imposed on the Punjab region and “Operation Blue Star” was initiated by Prime Minister Indira Gandhi in 1984 to arrest the followers of Bhindranwale, who had established a terrorist stronghold inside the Golden Temple. The temple was besieged by the army within five days and Bhindranwale was killed.

Casualties occurred among civilians, too, and there was serious damage done to the holy precinct. This caused anger amongst the Sikh population worldwide, since the Golden Temple is the most prominent holy site of the community. Conflict in Punjab intensified following the army assault on the Golden Temple and this fanned the flames of the violence between the security forces and the militant groups. This period also saw major political assassinations, including of Prime Minister Indira Gandhi herself. The Khalistan movement did not see the end after this, but has kept on recurring time and time again. When moderate leaders of the Akali Dal like Harchand Singh Longowal tried to make a peace agreement with the government of Rajiv Gandhi, he was assassinated by extremists who regarded him as a traitor.

Punjab’s crisis was a combination of social, political, and economic distress. Ironically, the prosperity in agriculture in Punjab post-Green Revolution was followed by a rise in class difference and unemployment. Punjab’s economy was lopsided because the rise in agriculture was not accompanied by parallel growth in the small-scale industry, which forced the youth to migrate to other places. Punjab now attracted semi-skilled and unskilled laborers from Uttar Pradesh and Bihar. The situation worsened when Sikh farmers and peasants felt that they were not getting their due and that much of the benefits of their efforts were flowing to other parts of the country. The economic and political crisis began to take religious overtones when parties like the Akali Dal started expressing their social demands in the name of religion.

There can be many lessons drawn when looked retrospectively, however, one consistent lesson that remains for the Indian state is to not undermine the insecurities felt by the minorities of the country. Political means can be drawn out of such insecurities and can lead to disastrous moments like that of the Khalistan movement in Indian history. Such neglect also carries the potential of a legitimate protest being appropriated by external or internal secessionist forces and, in no time, nullifies the actual problems faced by the people of the country.

Right on my man!

Right on my man!

Wonderful views on that!

Good thorough ideas here.You may want to actually consider a lot around the idea of french fries. What do you think?

Right on my man!