Since the dawn of civilisation, history has been about the winners. Editing and omitting the past has been the most common and handy tool to control the masses into submission and support the contemporary ruling power. Accordingly, all kinds of changes in the power (from new dynasties to new political parties) are mostly accompanied by an attempt to change the narratives of the past. As long as common folks are in agreement with the state about recovering ‘their suppressed’ history and culture, the state power needn’t worry about losing out to the ideological opposition.

The attempts to reclaim the past can be varied, ranging from renaming of famous monuments or infrastructures to modifying the education system. India has a long history of these kinds of changes in ruling power along with the destruction and establishment of new cultural past over the old. Here, we are going to discuss some of the most astonishing examples of altered narratives of the past belonging to a period of power struggle amongst the Mughals, the Britishers and post-independence India.

The Revolt of 1857 is claimed to be the First War of Independence which successfully intimidated the Britishers. This resulted in shifting their control of the Indian colony from East India Company (E.I.C) to the Monarchy of England. Bahadur Shah Jaffar II, the last Mughal emperor ruling at the time of revolt, reluctantly agreed to be the figurehead of the rebellion at the request of mutineers and their supporters. Therefore, symbolising that although Mughals were substandard in power around the 1800s, they were still the rightful rulers of India for the masses. E.I.C never bothered to break this illusion and continued to rule the economy without holding any political responsibility. However, all this was to change after the bloody clashes of 1857 which claimed lives of thousands on both sides, in battles as well as in the ruthless massacres. Thus, the Mughal emperor was ousted from power and all possible measures were taken to demonstrate to the public that Britishers were the new and true rulers of India.

In their bid to transform the revolt of 1857 from a black spot in history to a glorifying and patriotic event, Britishers resorted to whitewashing the event in all possible ways; geographically, historically as well as culturally. Graves of the ‘martyred’ British soldiers were dug all over Delhi aggrandising the circumstances of their heroic deaths (sacrifice for the protection of British rule) and omitting the embarrassing ones (natural deaths). Families of the patriotic soldiers were honoured and gifted land possessions of as many as 33 villages in districts of Delhi like Palam, Kotla, Wazirabad. Significant Mughal cultural centres inside the walled cities like Akbarabadi mosque, Urdu bazar, Khas bazar, Sunheri Masjid, Jama Masjid were either demolished or confiscated by the government. These agricultural lands and monuments along with antique treasure were appropriated as retribution for the troubles caused by the indigenous population. Even the Red Fort was transformed into a military space and modifications were made to suit the needs of the soldiers.

Imperial Durbar was held in Delhi in 1877 for the first time in honour of Queen Victoria being titled as ‘Empress of India’. It was figurative of British being the victors. This symbolic connotation of expropriating the seat of power of presiding emperor is further highlighted when one realises that despite Kolkata being the focal point of British power in India, Delhi was the place for Imperial Durbar. However, the looting and plundering allowed by the government in the aftermath of 1857 was definitely a sharp wound in the memory of public. Thus, there were also efforts to get back into the good books of masses. Places like Jama Masjid were opened to the public with rules and regulations while piertra dura panels behind Shah Jahan’s throne platform in Diwan’e Am, Hall of General Audience, were restored. The message was to convey that government is empathetic and understanding of the indigenous culture and heritage; appeasing them with a new lens to the past while pushing the painful memories of suppression in the dark.

Here, it is pertinent to note that the architecture built by British like the Lutyen’s Delhi, was reclaimed by Indian government post-Independence as the seat of power in the new era for the nation. Again, an instance of rewriting the history with new ink, symbolising the shift of power from the legitimate to illegitimate.

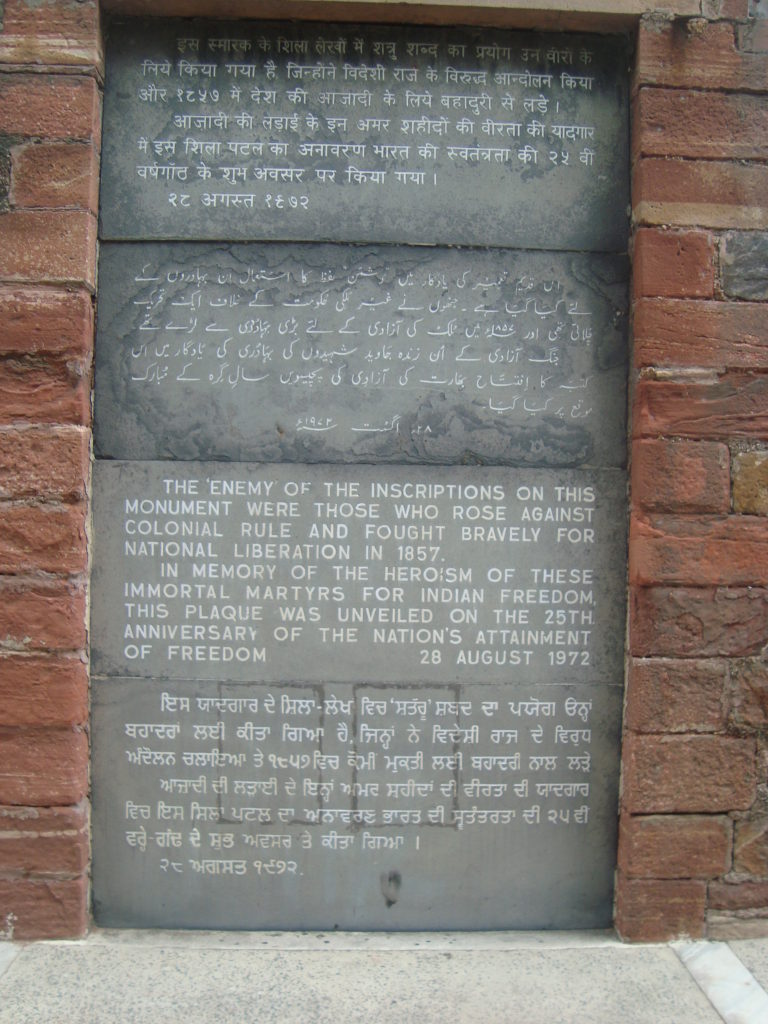

Another fascinating example along the lines of subverting the past is the Mutiny Memorial. Erected in 1863, this tapering red sandstone monument with its gothic design, marble backed recesses inset in all sides of octagonal tower, was built on the site of Taylor’s battery artillery unit which bore the brunt of rebel fire. The memorial appears to comprehensively set out the narrative of the Delhi revolt. However, the historical details are selectively inscribed; emphasising only on the ‘Englishmen’ and British officers and subsequently undermining the native Indian soldiers’ (and officers’) sacrifice, which ironically made up the majority of the police task force. This was considered to be the official mutiny memorial besides the various other grave stones and other minor memorials built in varying forms across the city.

After independence, this memorial became part of the government’s drive to appropriate British memorials by setting up inscribed stones at some places in order to memorialise the revolt. On 15 August 1972, Mutiny Memorial on Northern Ridge of Delhi was ‘converted’ into a memorial with the help of two inscriptions, ‘The enemy of the inscriptions on this monument were those who rose against the colonial rule’. Even the entrance of the monument reads, ‘for those martyrs who rose and fought against British during 1857 AD’.

Therefore, we can observe that manipulation of past and history in favour of those in power is the ultimate tool to legitimise their position and appease the thought process of the masses. These examples of attempts to refurbish the memories bring to light the common human tendency to forget the disgraceful and pass on the glorifying; paint a happy picture for future generations.An effort to divert the narrative to suit the personal agendas and gain from the subsequent shift in the recording of history is therefore not a new phenomenon. However, the frequency and ease with which this can be done should never be taken for granted. As long as we are aware and conscious of the fact that history has always favoured a side and is never completely neutral, there is hope in its reclaiming by the future generations, hopefully in a way that both sides are given an equally discerning lens.

The writer had just finished her M.A. in History from Delhi University and preparing for further studies. Exploring culture, society and learning about the various facets of humanity has intrigued her since childhood and thus she aspires to contribute her bit in making the world a better place.