India has seen some major environmental movements in the past. These movements have risen across different regions of the land – covering mountains in the north, to the serene south, and sedating northeast and around the major rivers of central India. These movements are usually seen under the idea of third world environmentalism as opposed to the first world environmentalism of the western nations. The difference between the two was being recognized and internalized, while environmentalism was discussed on different international platforms that saw global participation. It is said that this issue connects all the nations and brings us together. But is it so? It can be established as a fact that the extractive needs of every nation differ depending on the level of ‘development’ the country has gone through. So in this process of so-called development and modernization, third world countries can be positioned at that stage where environmentalism seems to be too luxurious to be accepted. We need industries; we need to extract our natural resources to sustain the given population. Indian environmentalist and political activist, Sunita Narain, distinguishes between ‘protectionist conservatism’ in the first world and ‘utilitarian conservatism’ in the third world referring to the dependence of a large section of people in the Third World on the environment for food, water, fodder, etc.

Scholars who wrote extensively on India’s environmental history, like Madhav Gadgil and Ramachandra Guha, who borrowed their arguments extensively from the American economist Thurow, argue that “environmentalism is an interest of the upper-middle class” and that “poor countries and poor individuals simply aren’t simply interested.” They believe that environmental concerns are like the next big luxury as it makes the other goods and services more enjoyable. “Greenness is the ultimate luxury for such societies,” they argue. This is seen in opposition to the environmental movements in the third world countries where the roots lie mainly in the problem of livelihood for the people of that region and the distribution of resources.

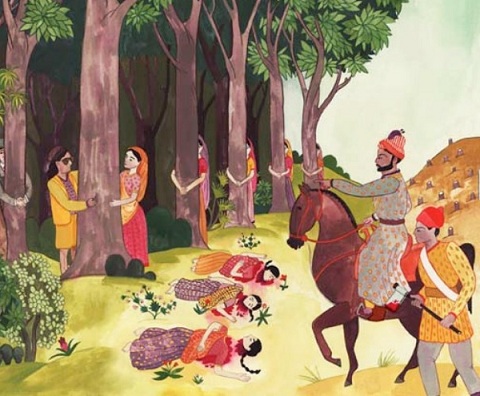

One of the oldest struggles to protect the environment, which continues can be seen among the Bishnois. Certain communities in Rajasthan belong originally to the land and are amongst the oldest civilizations excavated in India. They are well connected to their land and understand the need for a harmonious relationship with nature. Bishnoism is a religion which is said to have started in 1485 AD by saint guru Jambheshwar in the Thar desert of Rajasthan. The values of the religion were based on eco-conservation and wildlife protection. Three hundred years after the religion was formed and people of the community swore to the 29 principles, the Maharaja of Jodhpur ordered to gather wood from the forest near the village of Khejarli, where khejri trees were taken care of by the Bishnois. The Bishnois protested when the trees were being cut. From this time comes the story of Amrita Devi, who was just a female villager of the community. She could not bear the destruction of forests and decided to literally hug the trees and encouraged others to do so as well. As each villager hugged the trees one by one to protect them from being cut down, they were beheaded by the soldiers. When the king got to know about it, the royal orders were taken back, and the region was marked as protected. Harming plants and animals were forbidden. The inspiration of the Chipko movement, therefore, also comes from the Bishnois.

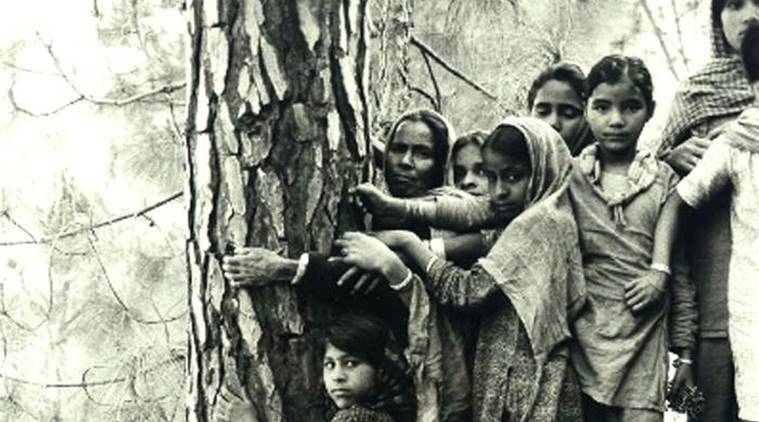

Chipko Andolan in India reminds us that it is not a human vs. nature war that environmentalism is dealing with. We need forests living in cities as much as the people living in the forests. The widespread movement that Chipko became not only targeted deforestation but took over other environmental concerns as well. It was a reality check for a society that did not work on a sustainable path and broke the ways of many communities in mending their own. The movement started in April, 1973 with the resistance of the villagers of Mandai, Uttarakhand, led by Chandi Prasad Bhatt, and the Dasholi Gram Swarajya Mandai (DGSM). They prevented the Allahabad-based sports goods company ‘Symonds’ from felling ash trees. The movement took a turn under the leadership of Sunderlal Bahugana, who began organizing Chipko activists for the tree felling in Henwal valley in 1977. This time the movement saw large-scale participation by women as well. This was also the point when the cause of the movement was raised from an economic struggle to an environmental cause. As it is said, “Behind Chipko lies a century of peasant protests against commercial forestry in the Himalayas.” After the Indian-Chinese border conflict of 1962, an extensive network of roads was built throughout the region that opened avenues to many entrepreneurs and governmental projects. Therefore the 1970s saw a dozen such confrontations in the Himalayas of Uttar Pradesh.

The 1970s also saw the silent valley movement in the Malabar region of Kerala. The area was the most under-developed region of the state, and the state was planning to build a dam for the Kunthipuzha River, which flows through the valley, to generate hydroelectricity as the basis for regional economic development. However, it was concluded that it would only lead to a marginal contribution to regional development besides also costing the biodiversity of the region.

The movement asserted that while the local environment will be disrupted, the benefits, instead of reaching the rural lands, will go to the capital. Further, the 1980s have also seen some major environmental movements, one of which includes Narmada Bachao Andolan. This movement was lead by activists like Medha Patkar, Baba Amte, Arundhati Roy, etc. under whom the movement targeted the building of two dams – one was Sardar Sarovar Project in Bharuch District of Gujarat, while the other was the Indira Sagar Project in Khandwa district of Madhya Pradesh. The movement opened the most heated debate of our times, that is, around the merits and demerits of building dams. Although the movement had been successful in downsizing the area that was being covered, the major success lay in the fact that people became aware of the cost at which the development comes. There is a sacrifice of lives and livelihood, the right to rehabilitation, and the whole biodiversity of the region gets disrupted. The issue was also severely politicized and therefore, gradually lost its focus.

Coming into the 1990s, post-liberalization saw many disputes amongst locals and foreign-funded projects. For instance, regional movements like movements against the POSCO, Chilika Bachao Andolan lake, and in the region Kashipur ( Orissa) garnered global attention. These local issues need attention for their legitimacy and strong support, wherein a global discourse attains the strength of their case through these local issues as well. While this process of feeding each other goes on, what gets neglected is the actual voice of the people who are affected. In the binarised discourse of the pro-state and anti-state, pro-development, and anti-development, we are leaving behind fewer choices for the affected people.