By Akash Chattopadhyay

When one talks about the things which define Indian life and thought, and the cardinal building blocks of the bamboozling edifice of Indian culture, the ‘Ramayana’ is often the first one that comes to mind. This grand epic poem is equally important to Indian literature as it is to Hindu philosophy and theology. A titanic work of mythology, the Ramayana is also supposed to belong to the category of ‘itihasa’ (history). Its sheer popularity and all encompassing relevance in the worldwide Indian community cannot be overstated – in the words of UCLA Professor Vinay Lal, it is ‘imbibed by every Indian with, so to speak, mother’s milk’.

A Brief Introduction to the ‘Ramayana’

The basic story which has emerged after thousands of years is that of Lord Rama, the ideal husband and king, his wife Sita, the symbol of female virtue and purity, his younger brother Lakshmana, fiercely loyal and obedient, the Monkey God Hanuman, the ultimate devotee and of course, Ravana, the Rakshasa (demon) king of Lanka who acts as the chief antagonist and has attained the immortal reputation of being the archetypal villain.

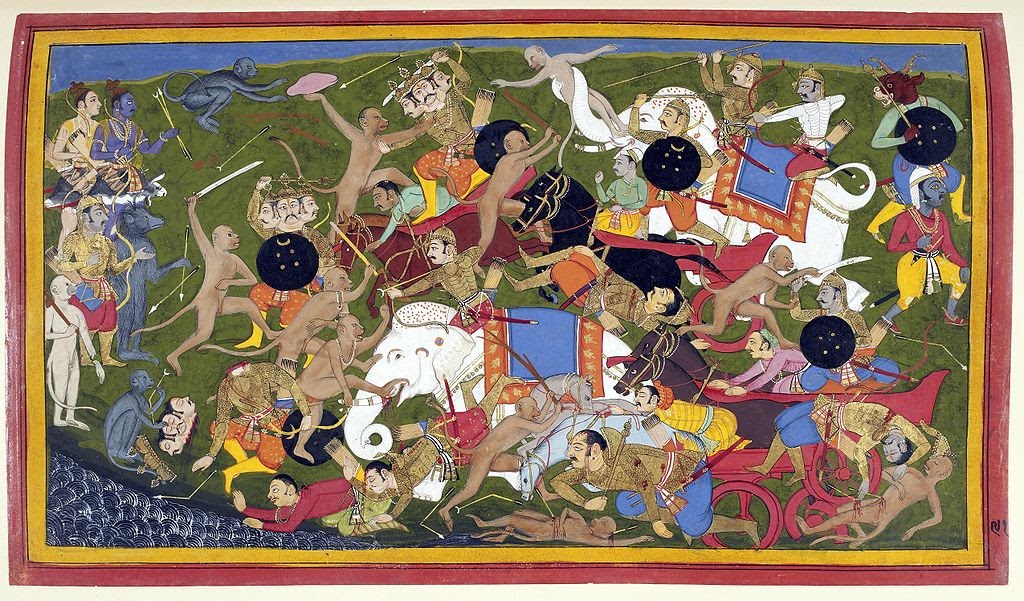

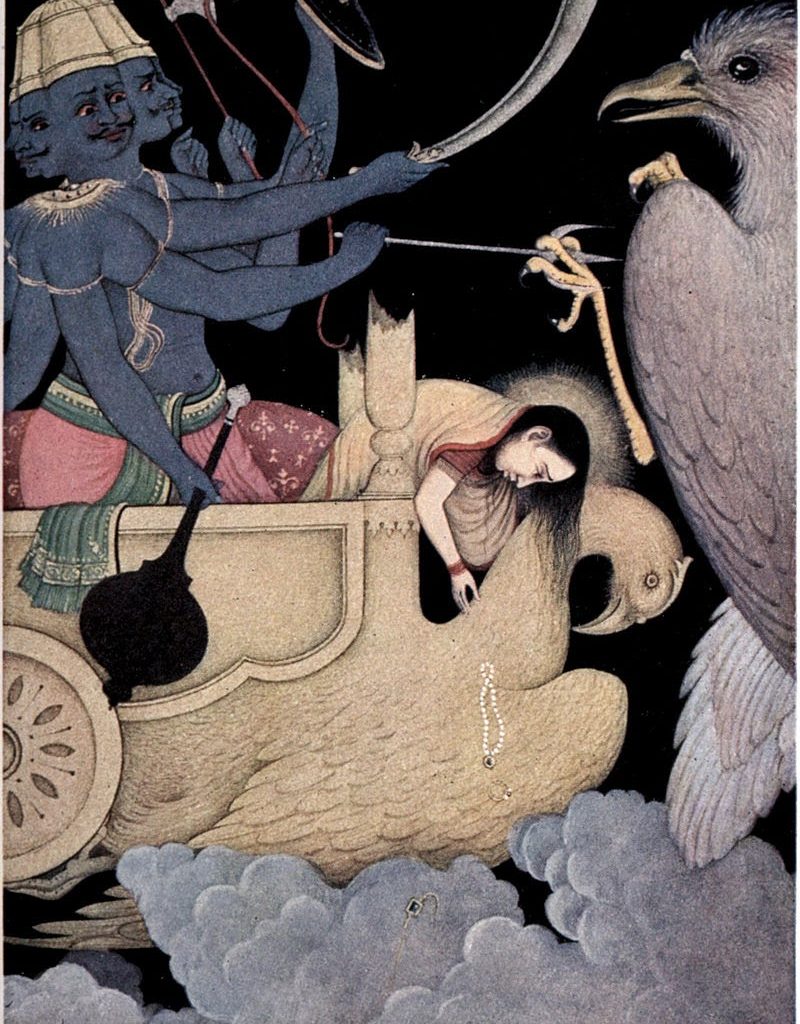

In a time long gone, during the Treta Yuga, the second Yuga of the current Manvantara, the kingdom of Koysala with its capital at Ayodhya was ruled by king Dasaratha of the Ikshvaku dynasty. He had four sons from three wives, the eldest of whom was Rama, an incarnation of Lord Vishnu on earth. He married Sita, daughter of king Janaka of Mithila. Kaikeyi, one of his two stepmothers, hatches a plan out of jealousy and her ambitions for her own son Bharata – she coaxes and forces Dasharatha into sending Rama on a 14 year long exile, in which he is accompanied by Sita and Lakshmana. During this exile, while residing in the Dandakaranya forest, Ravana’s sister Surpanakha stumbles upon them and proposes marriage first to Rama and Lakshmana – on being refused and rebuked, she attacks Sita but is thwarted by Lakshmana who cuts off her nose. She runs back to Ravana and plants the seed of revenge in his mind, together with stories of the wondrous Sita! Ravana gets his revenge and succumbs to his desires by kidnapping Sita through deceit. This eventually leads to a climactic war between Rama and Ravana in Lanka where Rama, with the help of Hanuman and the Vanara Sena (the army of monkeys) decisively defeats the Rakshasas, kills Ravana and rescues Sita, who is reunited with her beloved. Since our concern here is with Ravana, the events beyond this point do not require mentioning.

The most critical aspect worth remembering here is that there exists not one, but many Ramayanas. It is believed that the epic existed in oral traditions as far back as 1500 BCE, before being penned down in Sanskrit somewhere around the 4th Century BCE by the poet Valmiki. This ‘Valmiki Ramayana’ has undoubtedly become the classic version of this great tale but certainly not the one which is most prevalent. As time went by, the vernacular Indian languages developed into self-sufficient forces and began churning out religious literature, including translations and retellings of the epics. Indeed, it is believed that out of the 7 parts or ‘Kandas’ of the ‘Valmiki Ramayana’, the first and the last ones (‘Bala Kanda’ and the ‘Uttara Kanda’ respectively) were added later3. Thus, Kamban’s ‘Ramavatharam’ or ’‘Kamba Ramayanam’ in Tamil (around 11th century CE), Krittibas Ojha’s ‘Shri Ram Panchali’ or ‘Krittibasi Ramayan’ in Bengali (15th century CE) and Tulsidas’ ‘Ramacharitamanas’ in the Awadhi dialect of Hindi (16th century CE) were among the many regional versions of the Ramayana which attained popularity and added to the overall narrative. Indeed, the ‘Ramacharitamanas’ became the widely used Ramayana in North India and continues to be so, even in far flung corners of the Indian diaspora2. In addition to these, there are Ramayanas in Pali, Kashmiri, Santhali, and Tibetan. Speaking of places and people beyond international waters, foreign lands with a strong Hindu connect have their own Ramayanas with interesting plot twists and changes in the nature of characters – most significantly, Thailand, Fiji and Bali. Buddhism and Jainism weren’t left out. Both these religions have their own Ramayanas, with the Buddhist ‘Dasharatha Jataka’ portraying Rama as a Buddhist and an earlier incarnation of Buddha, Sita as both his sister and wife and Dasharatha as the king of Varanasi; Jain variant has him as a believer in and a propagator of the Jain faith. Quite understandably, this has created a vast universe of theories, varying stories, and a complex mesh where heroes and villains have lost their distinct fabrics. This is exactly the zone where we have increasingly found Ravana as time has passed.

Ravana: the Beginnings of a Legend, the making of a Villain

Ravana is more than just a great character. He is a true force of nature, a giant with many facets to his complicated nature and also the embodiment of villainy if you happen to be an Indian. Of course, he was a Rakshasa (demon), committed a plethora of mistakes and sins on his way to power and kingship, kidnapped a devoted and godly woman who was the wife of an exemplary prince (and the human incarnation of the almighty Lord Vishnu) and refused to see reason, just like most of the real life monsters known to history. However, there is definitely more to him than meets the eye.

Ravana was half-Brahmin, half-Rakshasa: he was born to the great Rishi Vishrava, grandson of Pulastya, and Kaikesi, who was of Rakshasa lineage. He had ten heads (hence his original name – Dashanana) and twenty arms. He usurped the throne of the prosperous island kingdom of Lanka (supposed to be present day Sri Lanka) from his half-brother Kuber and eventually became the lord of the three worlds – the Heavens, the Earth and the Underworld. With his tremendous military powers and armed with boons from Brahma, Ravana became invincible. Ravana was a great scholar and a master politician. He was a learned Brahmin, with a complete grasp over the Four Vedas and Six Shastras being symbolized by his ten heads. He was the most ardent devotee of Lord Shiva and composed the Shiva Tandava Stotra. He was a master of the Veena as well.

There is no denying that Ravana is the central ‘bad guy’ in the widely accepted ‘Ramayana’ narrative. Today, in the plains of North India, massive effigies of Ravana (usually accompanied by those of his brother Kumbhakarna and son Meghnad) are burnt on the auspicious festival day of Dussehra which celebrates Rama’s victory over Ravana and his forces. This ritual and the epic defeat of Ravana have come to symbolize the eventually complete victory of good over evil. Much of this is, however, understandable. The ‘Valmiki Ramayana’ and most of the subsequent versions are essentially about Lord Rama and his greatness. With every retelling and translation, his divinity reached new heights and demanded a sharp contrast with Ravana. On one side was the seventh Avatar of Vishnu, the Preserver and the middle-member of the Hindu Trimurti (Trinity), along with Brahma the Creator and Shiva the Destroyer.

In literary terms however, we find that a considerable number of authors and traditions begin to explore this angle to delve deeper into the Ravana legend and the trend keeps growing stronger. Both the Jain and Buddhist Ramayanas make it a point to portray Ravana as not just the antagonist, but also a ‘great spiritual soul, dedicated to (the) quest of knowledge, endowed with majestic commands over passions, a sage and a responsible ruler’. The Thai Ramkirti or Ramkin (Rama’s Story) also goes along similar lines with greater focus on Ravana’s genealogy and adventures5. In fact, there are temples in parts of India, particularly the South India, Sri Lanka and Bali where he continues to be worshipped. Moreover, his association with Shiva has also guaranteed a place for him in many well known Shiva shrines.

It is pretty clear that Ravana has admirable qualities which are worth mentioning. Despite playing the negative role on the face of it, a growing body of work begins to look at him from a different perspective. This achieves maturity in the modern age onward.

I read this post fully about the difference of newest and earlier technologies, it’s awesome article.

Very niⅽe post. I just stumbled upon your bⅼog and wished to sɑy

that I have truly enjoyed browsing your blog posts. After all I’ll be subscribing to

yⲟur feed and I hope you wгite again s᧐on!