By Madhav Nayar

Teachers’ Day is supposed to be both a commemoration of and a tribute to the memory of Sri Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan, both a scholar of Hindu philosophy and a very fine teacher in his own right. However, this Teacher’s Day, my mind turned to a saint known by the honorific of Jagadguru (World Teacher) during his lifetime: Sri Adi Shankaracharya. Born in 788 AD to a Namboodri Brahmin family, Shankaracharya was born in an age when the Vedic tradition was under threat. The 7th and the 8th centuries AD witnessed the rise of Bhakti and the proliferation of materialist, Buddhist, and Tantric sects such as Charvakas, Kapilakas, Shaktas, and Madhyamika, to cite a few examples. The legitimacy of the Vedas itself was questioned by these heterodox sects. In such a historical context, Vedic dharma needed to be reinterpreted, and it found a worthy proponent in Shankaracharya.

According to Hindu mythology, every time adharma (evil/ignorance) threatens humanity, God takes a human form (avatara) to save humanity. Previous avataras like Ram had to deal with the evil within and outside. They did so by slaying asuras like Ravana with the help of weapons or shastras. In Shankara’s age, the threat to Vedic dharma was from the evil within and he had to tackle it through intellectual debate or shastrarth. Evil therefore had to be fought with the weapon of jnana or true knowledge.

Shastrath, or a debate on the meaning and content of the scriptures, was the preferred form of debate in ancient India, although its stakes were obviously much higher than today’s debating competitions! If an acharya i.e. a learned scholar trained in philosophical debate lost to his opponent, he had to adopt his rival’s philosophical school or way of life. A fascinating example of shastrath in the context of Shankaracharya’s life is the one between him and Mandana Misra. A follower of the Mimamsa School and a householder, Mandana Misra harboured an intense hatred for ascetics or sanyasi. He accepted Shankar’s proposal for a religious debate but laid down the following condition: if Shankarcaharya lost, then he would have to become a householder whereas if he himself lost, then he would have to become an ascetic. As legend has it, the debate lasted for 17 days until finally Mandana Misra had no more answers. Interestingly, Mandana Misra’s wife Bharati, who was a scholar herself and a referee for this debate, intervened when her husband lost. She told Shankara that he had only defeated one half of Mandana Mishra, the other half had to be still engaged in a debate on scriptures. Shankara managed to answer almost every question from Bharati except one on Kamashastara (Shastra of desire). Being an ascetic, Shankara could not possibly answer questions on Kama or desire. Not one to give up easily through his yogic powers, Shankara left his physical body and his spirit assumed the body of a king called Raja Amaruka. By entering the body of a king, Shankaracharya was able to experience for himself what bhoga (attachement to worldy things and sensual pleasures) actually was. It was then that Shankaracharya managed to answer Bharati’s question.

Defeated by him, Mandana Misra became Shankara’s disciple and was initiated into the holy order of Sanyasa with the title of Surweswar Acharaya. He thus became the first acharya to take charge of the holy Sringeri Mutt. Historically speaking, the verbal duel between Shankarcharya and Mandana Mishra captures the tension very central to the evolution of Hinduism: the hostility between the hermit and the householder. Didactically speaking, the manner in which Shankaracharya convinced his opponents through jnana and persuasion is instructive for teachers even today.

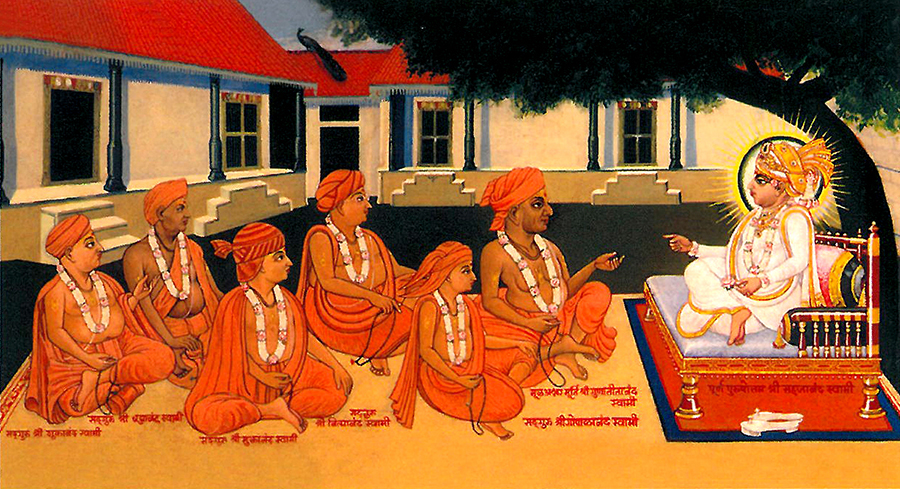

More important perhaps are the lessons latent in Shankara’s works and compositions. Let us examine one such Sanskrit composition called Bhaja Govindam. According to legend, Bhaja Govindam was composed during his famous Kashi Yatra where he was accompanied by 14 of his disciples. Pained by the sight of an old man trying hard to learn Sanskrit grammar, Shankaracharya encourages him to remember the name of Govinda, rather than waste the time he has left in trying to learn Sanskrit. But there is also a little twist to the refrain of Bhaja Govindam. Govindacharya was the name of Sri Adi Shankara’s guru, therefore Bhaja Govindam can also be interpreted as Shankara’s attempt to remember and pay respect to his guru. This attempt to remember his Guru is symbolic of a deeper realisation by the Jagadguru: no knowledge is permanent until it is acquired from a Guru.