By Piyush Kukrety

The Ramayana and Mahabharata are a part of the genre ‘Itihaasa’ of the Indian literary tradition. Though literally translated as ‘history’, the term Itihaasa has come to be seen from a variety of perspectives over time. It is seen that the notion of ‘change’ is crucial in these perspectives.Repeated emphasis is laid on how inevitable and immutable the law of change is. In both the epics, divinity manifests in the earthly realm of the mortals, which is subject to the limitations of time and space. The Ramayana and Mahabharata are vastly distinctive stories, and this can broadly be attributed to their markedly different historical setups. In Hinduism, ‘Yuga’ is an epoch or era within a four-age cycle. A complete Yuga starts with the Satya Yuga, via Treta Yuga and Dwapara Yuga into a Kali Yuga. The Ramayana is set in the Treta Yuga, while the Mahabharata takes place in the Dwapar Yuga.

Vishnu incarnates as Lord Rama in Treta Yuga to uphold the dictates of the Varna-Ashrama Dharma. He conducts himself in strict adherence to what are believed to be the ‘rules’ of an ideal life. In fact, it is interesting to note how Lord Rama’s ideals at times undermine the basic tenets of human morality. His act of asking Devi Sita to undertake the Agni-Pariksha and ordering Her to be abandoned in the forest due to street gossip has been a highly questionable action. Therefore, for Lord Rama, adherence to the dictates of societal injunctions was supreme. The purpose of His incarnation was to uplift Dharma, but at the same time assure people that this can be done by adhering to the rules laid down by society. It is also a widely held opinion, that Vishnu’s incarnation as Rama represents an attempt to seek a ‘redemption’ from the ideals He upheld in His previous incarnation as Parashurama. Though born as a Bhramin, Parashurama never lives up to the stature a Brahmin is associated with. He wields deadly weapons and massacres the Kshatriya race. This he does because the Kshatriyas having amassed immense power over time, begin to torment the world. Lord Rama, on the contrary, is born as a Kshatriya and makes it evident that the role of a Kshatriya when undertaken to keep in mind Dharma, is indispensable for the harmonious existence of all beings.

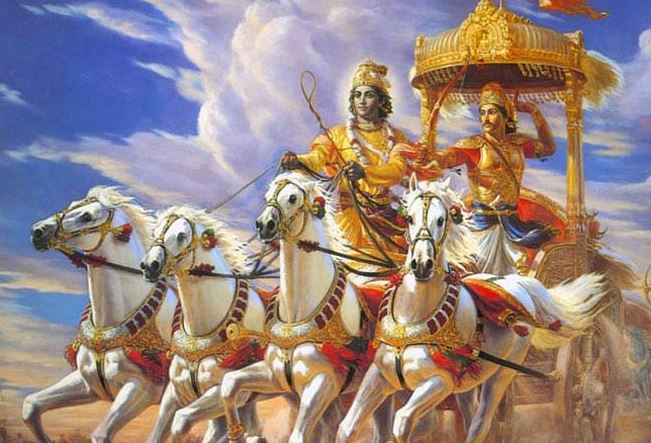

The time frame in which Krishna takes birth is strikingly different. The Dwapar Yuga represents a significantly evolved and advanced society when compared to Treta. Societal injunctions, though still present are seen to be disregarded at several points of time. being wholly truthful was no longer a desired trait and valiance competetiveness became the norm. Krishna, the eighth incarnation of Lord Vishnu, is also born as a Kshatriya but is raised among cowherds, a Vaishya caste. He goes on to defeat the tyrant Kansa and establishes a kingdom with Dwarka as its capital city. Thus, we see that His Kshatriya status lives on, despite having being raised in a Vaishya household. In the Mahabharata, it is seen that the ideals of Varna-Ashrama are disregarded in several instances. Bhishma, in his youth, when he is ideally supposed to be leading the life of a householder, takes a vow of celibacy. Karna who is believed to be of lowly birth is made the king of the province of Anga, Draupadi is simultaneously married to five men when monogamy was the norm, all of which clearly reflects that over the years, the perception of what is ‘ideal’ has significantly changed.

In the Krishna Avatara therefore, Vishnu bears testimony to the fact that with the evolving times, the means of protecting Dharma also need to evolve. The circumstances in Dwapar are such that mere adherence to rules is not sufficient in defending Dharma. It is therefore seen, that at several points of the war, Krishna bends and at times even breaks rules. He, however, does this with a higher goal and objective in mind.

An understanding of the epic tradition cannot be developed unless the centrality of the notion of change is duly understood. If one is to trace the historicity of political thought in the epic tradition, there is no better starting point than developing this understanding.