By Arushi Kapoor

Passing down stories and even knowledge to posterity through oral tradition has been in practice since ancient times. The Shruti and Smriti traditions in Hinduism refer to “that which has been heard or revealed” like Vedas and those “constructed and evolved over the period of time” respectively. However, both traditions involved oral teachings and the written records didn’t emerge till thousands of years later. One might wonder how such long and complicated texts were learnt by heart and passed on further. Few answers to such questions could be obtained by analysing some of the surviving oral practices in several fascinating pocket cultures across the country.

Bengali bards wandering with their picturesque scrolls, going from one village, town to the next wasn’t such a rare sight till a few decades ago. In the absence of cinema, television and internet, such storytellers were one of the biggest sources of entertainment. One such tradition, known as Pabuji ka Phad, still survives in Rajasthan near Bikaner around a small village called Pabusar. The story revolves around a local hero Pabuji who was gradually transformed into a deity. Being a folklore which was born in a primarily pastoralist community surviving in arid desert, Pabuji was thus hailed to have saved the cattle in battle or from thirst on various occasions. Their local deity was the one who made it a point to look after all their survival needs. Therefore, in this way a local hero who apparently was a historical figure to have lived in the fourteenth century was transformed into a local god. This was owing to the kernel of historical truth of him having fought off the oppression of upper caste Brahmins and Rajput, thus, a figure with whom the community was able to connect on their own level. While the devotees accepted the importance of overarching Gods like Brahma and Vishnu, it was Pabuji to whom they appealed first in times of local crises.

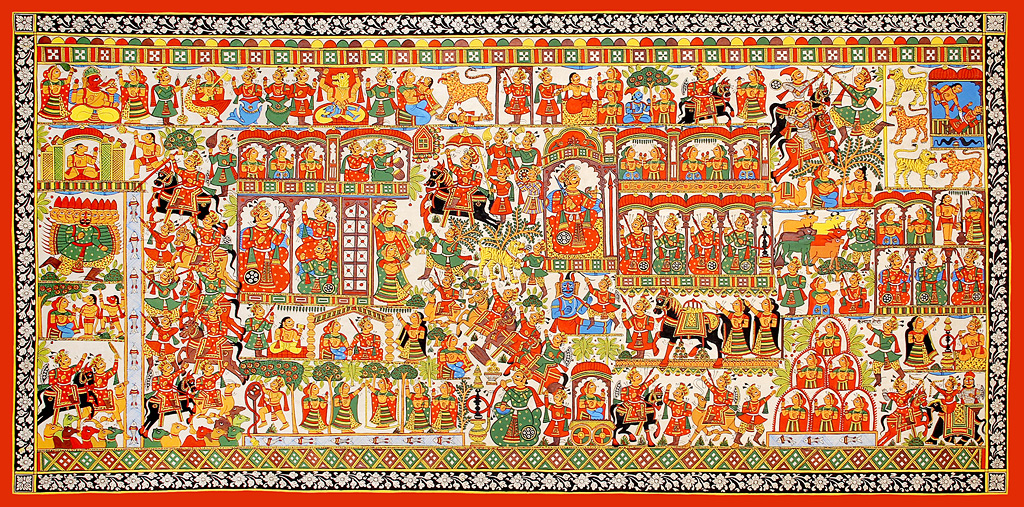

Pabuji ka phad involves performing for consecutive nights, starting after sunset and pausing just before dawn. It is performed by a local artist known as bhopa along with his wife and might include their children as well. The epic is always performed in front of a phad, a long narrative painting made on a strip of cloth which serves as both an illustration of the highlights of the story and a portable temple of Pabuji, the God. Interestingly, in such a scenario, the picture is elevated to the status of an incarnate murti(idol), equally pious to an image in a temple. If a person wants to pay respect and seek blessings from Pabuji, the designated bhopa is called upon to perform at the devotee’s house with the sacred phad. The art of making the phad is in itself considered a sacred work and once completed (making eyes of the deity being the last step), it is to be treated with utmost respect and taken care of like a murti in a temple, meaning it is supposed to be possessed with the divine spirit and blessings of Pabuji. At the time of disposal too, the phad is decommissioned and is offered either to the holy waters of Ganges or the Pushkar Lake. The recitation also involves singing of bhajans in breaks, dancing and use of musical instruments like ravanhattha.

Besides owing to the belief of Pabuji being the protector, the bhopa also acts as a shaman to cure the diseased cattle or to ward off bad luck and evil spirits. On these occasions only the necessary part of the epic is recited according to the need. However, with the onset of improved technology and awareness, some have started to prefer doctors and veterinarians. Despite this, as one of the bhopa, Mohan ji, claimed the biggest threat to the tradition is the practice of writing. Once a person becomes literate, the ability to remember is diminished to a large extent. The psychology of always having backup written material to lean on to provides enough leeway to allow him/her not to learn the epic by heart. Also, with increased awareness, while on the one hand people are gaining knowledge about the existence of such pocket traditions, there is also an attempt to record the homogenised popular versions ignoring the subtle variations. This may result in only static survival of such cultural practice is some state archives, being revived only for research by scholars.

Combined with the above stated facts, the fast-moving materialistic lifestyle along with easy entertainment access through TVs, internet, etc. has drained the patience out of the next generation to sit for long consecutive nights and watch recital of a single epic. In few instances where they sit, the bhajans are now being replaced by demands of latest Bollywood songs. In the lack of historical context and aesthetic understanding, traditions like Pabuji ka Phad are one on the verge of being lost in time. While recording them would ensure that they still continue to exist as a part of nostalgic simpler times, one would never be able to recreate or experience the actual excitement only possible with live audience for whom these recitals are not a source of their entertainment but a part of their daily lives. The pride one feels in relating to a deity who was one of them and thus the validation to their otherwise monotonous life are few aesthetic lively experiences left in a world which is advancing towards a mechanised living.

The writer had just finished her M.A. in History from Delhi University and preparing for further studies. Exploring culture, society and learning about the various facets of humanity has intrigued her since childhood and thus she aspires to contribute her bit in making the world a better place.