Suraj Girijashanker is a specialist in international human rights law and international refugee law, currently teaching at Jindal Global Law School. He used to work as a legal advisor with the Immigration and Protection Tribunal in New Zealand and as an Expert on Mission with UNHCR Turkey. Suraj was also the Associate Refugee Status Determination Officer with UNHCR Egypt and represented refugees at the Australian Government.

Thank you so much for agreeing to this interview. To begin with, what inspired you to enter the field of refugee law?

Alright, I was always interested in human rights and social justice more broadly. But I think when I was a law student, I didn’t really know what that career path would look like. All my colleagues at the university were aspiring to be commercial lawyers. So, it was in my final year that my best friend convinced me to take a human rights course. I was actually going to take medical law because I had heard it was easier to get grades, not that I was interested in medical law. And until that point, I didn’t really feel anything for the law but when I took that human rights course, I was like okay, I can really get down to these issues and I think it kind of stirred the sort of this passion I guess in me. My family’s based in Australia so as you know, Australia…it’s sort of notorious for the treatment of refugees and it’s a really politicised issue. So, when I returned to Australia after university, I was just really keen to start working with refugees and that’s where it started, I think, the debates around refugees every election and the fact that refugees were demonised for me, something which made me really really angry. And my family are migrants to Australia. There is this distinction which is drawn between good migrants and bad migrants, even within migrant communities in Australia. “Oh, you didn’t come here through the legal way”, that sort of discourse and narrative which just really made me very angry. So yeah, it sort of stems from there.

Oh, that’s nice to know. You’ve travelled a lot for work, and you’ve stayed at different places, which experience would you say was the most enlightening? Any one in particular.

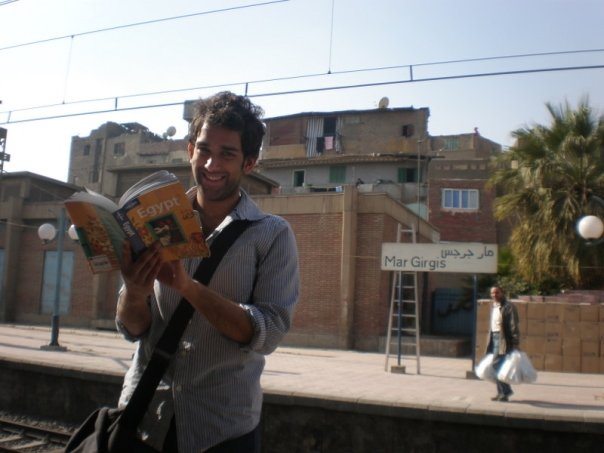

I think it’s quite clear, it’s the experience no one talks about in my job interviews. So shortly after I graduated, I moved to Egypt to work with a refugee legal aid organisation. So, we provided representation of refugees before the UNHCR which was in charge of determining who was a refugee and who wasn’t. And I think what was really special about this experience is number one, I was young and enthusiastic but also it was a really rare organisation because when I was working there, I was an advocate for refugees’ rights. I wasn’t someone deciding their case, I wasn’t someone sitting in an office writing a report about their situation. I really got to see first-hand what are some of the challenges refugees faced. It was really about the amount of time we could spend with our clients. So, to get to the UNHCR office which is outside Cairo, you’d be stuck in traffic for two hours with your client. Sometimes, you’d have to use public transport with them and then you’d wait sometimes, it would be the end of the day for their interview to determine whether they’re a refugee or not. I think what was also really special about that organisation was we had a lot of refugee staff and we had a lot of Egyptian staff as well and often I think, there has been a hierarchy between international staff, local staff, refugees. And that organisation was unique in that sense. Sort of more broadly about human rights, why I think this experience was so prominent for me. I really got a lot of time to spend with my Egyptian colleagues and it was Egypt post-revolution and many of my colleagues had engaged in protests against the government. It really made me think about, what does it take to be someone involved in human rights. It really made me critique and question my role in this at all. So, it was a really crucial experience.

The 1951 Refugee Convention defines a refugee as: “Someone who is unable or unwilling to return to their country of origin owing to a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group, or political opinion.” Considering that this definition was drafted around 70 years ago, do you think that we need to broaden the scope of the definition to make it more inclusive and dynamic considering the kind of displacements happening around the world?

I think if you ask most refugee lawyers or experts in this field, they’d have two views depending on what’s ideal and what’s pragmatic. So ideally, of course, you’d have a more inclusive definition. The definition we read was created in a different time, predominantly with the inputs of states from the West and the Global North. So, has it really taken into account the displacement in the Global South? Not necessarily. But practically, would States agree to a broadened definition? Possibly not given the xenophobia and stigma which is associated with refugees. Today I think if that definition was put on the table again, the states would try to narrow it down. I think the way to go about it is through case law, so the definition, the way it has been interpreted, has broadened out with case law. But there is some population which is incredibly difficult to fit within that definition. For example, folks who are fleeing due to climate change, or who are displaced due to climate change. It gets pretty difficult because often the countries where they are coming from are taking initiative and measures to protect their citizens from climate change which again goes against the conventional idea that you need to be facing harm from your state or your state’s inability to protect you from that harm. Often in these situations, the states are trying to protect their citizens from harm. So, I think, in addition to the refugee definition, we need to have alternate avenues for those who might not fit within those definitions, alternate programs for example, those fleeing due to climate change. But when we talk about the definition, it has evolved. Today, you do have many claims based on gender and gender is not a conventional ground but it is something that has been expanded and evolved with courts. I hope that it will continue to evolve and it’ll be more inclusive or take into account the realities which refugees usually face, which the original definition as we literally interpret it might not.

COVID has brought the world economy to a halt like never seen before and as we are already witnessing the have-nots being crippled by the loss of livelihood. How can we mitigate the impacts on refugees across the world? What can be done with regard to refugees in India?

First, I think there has been difficulty garnering services and access to services. Second, there are many refugees working in the informal sector and this presents a whole bunch of challenges. Third, when we’re talking about resources, for example, aid and rations, it has all been difficult to access those rations and services through aid. On top of that, you’ve got xenophobia, you’ve got refugees being blamed or certain sections of the population being blamed for what’s going on which is completely unjustified. Different groups have different challenges, so it’s important to keep the challenges of the refugees on the agenda because, in this time, we’re all facing difficulty, I think it’s kind of easy to forget that migrants or refugees would be having issues. So, I think that’s the first step.

The second step, if someone really wants to take that initiative, there are many refugee community organisations based in India who you can reach out to, find out what they’re doing and find out how you’d be able to help. If the refugees own businesses, support that sort of business. In Delhi, for example, there are some great restaurants and catering services they’re. If they are open, we can try and contribute to those businesses. These are small ways in which we can mitigate the situation [impact on refugees due to COVID] little bit.

According to the UNHCR (2009-17) data, a total of 364 outbreaks of infectious diseases have occurred in refugee camps of 21 countries. Malnourishment, poor sanitation and overcrowding is considered to be a cause of the outbreaks. What impact will a disease this infectious, leave on the lives of refugees, and will the nations be able to cope if/when COVID reaches those settlements?

I think when the pandemic sort of started, people had fears that it would reach the settlements and it has, particularly, Cox’s Bazar in Bangladesh. There was a lot of fear on that and now there are cases there, which is going to be very challenging. There isn’t sufficient funding for refugees in campsites. Every year there are calls for funding and the financial assessments which aren’t met. What’s challenging about camps is the fact that you’ve got such a high population density. To give you an idea, Cox’s Bazaar and the camps there, the density is higher than cities like New York. So, you can imagine what that spread is going to look like. There have been initiatives that have been taken. So, for example, isolation wards, social distancing really is a luxury there. But within those resources which are available, the UN and the implementing partners are taking initiatives. I think a key way forward is that these funding needs are met which again is really challenging as governments themselves are struggling to deal with the situation of their own population. But again, we need to keep the issues of refugees on that agenda so that they don’t slip off the radar and people don’t forget that people in camps are facing a really particular challenge given how constrained and dense they are.

Refugee situations are almost always political issues, as you also mentioned the case in Australia where you are located right now, which kind of stifles humanitarian concerns of the refugees. What would you say about it in general and specifically in relation to India’s approach in dealing with refugee situations?

Yeah, so when people think about India’s history with refugees, the narrative that has been pushed forward is that India is very welcoming to refugees and India has, in fact, many people have sought refuge in India. But what I would say is that this isn’t for purely humanitarian reasons. I think there’s definitely a political aspect to this and you can see that in the distinction in treatment between different refugee populations. There’s a bunch of ad-hoc agreements which govern different refugee populations in India. The rights which are available to Sri Lankan Tamils are not necessarily available to Tibetans or vice-versa.

And then, you’ve got other populations as well in smaller numbers. So definitely I think politics is something that we need to critique and we shouldn’t pull ourselves and say that it is purely for humanitarian reasons because it’s not. I mean when we talk about Tibet and Sri Lanka, there’s clearly a foreign policy angle to this. Anyone who is looking at refugee law and policy in India needs to look at it from this lens.

India’s refusal to comply with the principles of non-refoulement has led to a cul-de-sac with refugees. How can that situation be managed?

I think this is a very challenging question, there have been several cases challenging this. Let me first tell you what the Indian government’s position is. The Indian government’s position is they’re not a signatory to the Refugee Convention. This is one of the arguments that they make. So, they’re not bound by non-refoulement under customary international law, that’s clear cut but India’s party to other international agreements which sort of solidify this right of non-refoulement and what’s interesting is when you look at India at an international stage, they critique other governments for sending back people under risk to their country of origin. India has critiqued Australia; India has been an advocate against this sort of situation happening with the EU-Turkey deal. Given this history, I would hold that India can practice what they’re preaching.

CAA’s enforcement has generated a lot of controversies all across the globe. What is your take on that in reference to the refugee situation in India?

Again, I’ve seen this narrative sort of emerge like it’s a humanitarian law which I completely don’t agree with. I think it’s discriminatory. When you look at the law it’s not a substitute at all for refugee law and policy. Clearly, there are political motives for this law and the hypocrisies of the law have been highlighted time and time again. When we’re talking about religious minorities, is that the only sort of persecution people are fleeing from? No. For example, if Pakistan, you’re an Ahmadi, you can be at harm. Why are not Sri Lankan Hindus not included in this? I think there are a whole bunch of issues that are included in this. So, let’s look it up in that sense, we should not believe the narrative that this is for humanitarian reasons. It’s incredibly concerning because it goes against the secular ethos we would like to believe India has.

The LGBTQ+ community has been subjected to violence and discrimination for a long time. What additional difficulties do they face as refugees in countries which do not even recognize their rights?

Most refugees, as you might be aware, in the neighbouring countries are in the Global South and there is a disparity in laws which protect LGBTQ people in the North and the South. Whether we like to admit it or not, you can look at any map in criminalisation, there is that sort of divide. LGBTQ refugees do face specific challenges. I think if you’re in a camp based setting, you can be ostracised and really excluded. In urban settings, that stigma is there, in terms of employment opportunities. Many LGBTQ refugees I worked with have to engage in sex work to survive. There’s definitely that sort of stigma and in these countries which have got hostile laws against LGBTQ people. If you’re a citizen of that country, of course, there are risks to you, but they are only aggravated if you are a refugee. From my experience as a refugee lawyer, I think what’s concerning is that people who might be very progressive and have humanitarian values sort of, more broadly, when it comes to refugees don’t necessarily apply that to LGBTQ refugees and I’ve seen first hand in interviews and the sort of questions that LGBTQ refugees are asked. For example, there is an overt focus on sexual history and sex lives as proof. How does it prove that you’re an LGBTQ person? Very invasive lines of questioning, which I think is something that needs to be moved away from, which is again a really gradual process.

What message do you have for young people in India? Which steps can they take if they wish to work in the field of refugee law?

With refugee law specifically, I would encourage youngsters and students to get practical experience working with refugees. It’s one thing to study something academically and a situation academically. But if you haven’t interacted with refugees or in organisations that do not have that hierarchy or at least try to create a level ground between refugees and advocates; I think that would be a good starting point but more broadly for folks who are interested in social justice and human rights. I think that it’s important to constantly critique and assess where you stand in any organisation or institution. What is the role you’re playing? What are the politics of that organisation? Do they align with your views? You may never find an organisation which entirely ticks all your boxes but you do need to keep questioning. I’m still questioning today. what I’m doing, whether I am actually making an impact. Keep questions, that’s what I would say.

Thank you so much for taking out your time for us. It has indeed been a very insightful conversation about the nitigrities of the refugee lifestyle, refugee policies and the prospects of refugee law as a working sector.