By Hiral Goyal

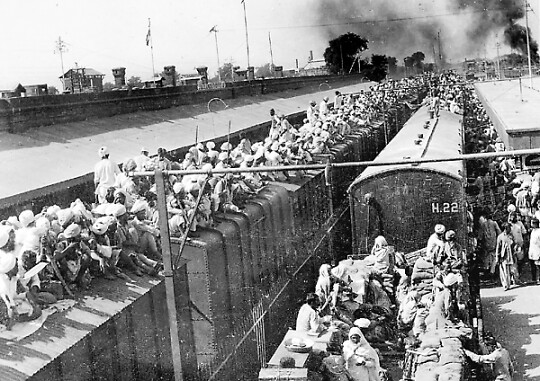

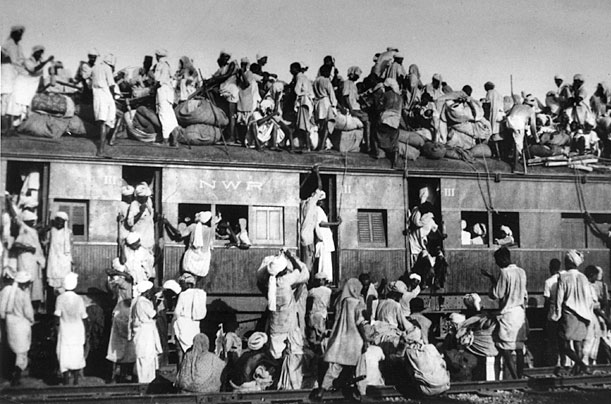

The 1947 Partition of the Indian subcontinent led to the largest mass exodus in world history wherein millions of people found themselves displaced. For a very long time, people had believed that the division of the subcontinent into India and Pakistan would be an affair limited to the legal papers. So, when the migration began, there was utter confusion and disorder around them. After the partition was announced, many of the families had to leave behind their homes overnight, choosing to carry only what was necessary and move across the border. People travelled either on foot in long processions known as kafilas or trains but more than often, they would be attacked on their way and families would be broken up, women would be abducted and raped, while men would be killed. According to reports, nearly 75,000-1,00,000 women were abducted and raped and sold off to buyers. They were made to convert their faith and marry their buyer.

Survivors of the Partition have often said, “Those times were bad, not the people.” Yet that was the period of violence and despair for the North-Western part of the continent where riots would breakout; very often leading to mass murder with the intention of ethnic cleansing, violence in the form of rape, mutilation of the genitals, forced marriages, abortions, etc. In Indian society, women have always been the physical embodiment of the “honour” of the community, the family, and the religion. When the Partition brought out the worst of humanity in Hindus, Muslims, as well as Sikhs, they resorted to violence committed on the body of the woman to taint the collective “honour” of the other community. While our history textbooks do tell us the chain of events that led to the division of the land, they do not, however, acknowledge the brutality and cruelty that people of all three communities committed upon each other. At this time, women would be abducted by men from other communities and raped, forcefully impregnated in an attempt to pollute their blood race and future generations. Some women tried to save themselves by committing suicide and some women were killed by their own family members so that their “honour” could be preserved. In her book, The Other Side of Silence, Urvashi Butalia provides an account of men like Mangal Singh and Bir Bahadur Singh who killed 17 and 26 members respectively of their own families (women and children) to protect their “honour”. These murders were usually glorified as sacrifices and the women were called “martyrs” for sacrificing their lives.

After the Partition, the governments decided that the abducted women be returned to their respective homelands. Thus, on December 6, 1947, an inter-dominion treaty Central was signed between Indian and Pakistan and a Central Recovery Operation was set up with women social workers and police officers. Under this operation, Mridula Sarabhai, Kamalaben Patel, and many others worked on both sides of the border to help women return to their homes. Although their aim looked simple enough, they faced a lot of unprecedented hurdles on their path. Most women who had been abducted were now married to their kidnappers and had a family. Others had been raped and were either pregnant or had given birth to children. While most women of both communities refused to return, their prime concern was that now that they had been “polluted” by the other community, their families would no longer accept them and they were right. For Hindus especially, who placed purity of their blood and race above everything else, it was next to impossible. At this time, the Prime Ministers of both countries were imploring their citizens to take back their daughters and wives, to bring them home.

However, the Operation had several shortcomings. Women were usually forcibly taken back to their homeland despite their wishes. Most of them were aware that their families would either be dead by now or unwilling to take them in. In fact, for many of them, their second or forced marriage was just like any other. It was not like their consent would have mattered anyway. The only difference was that they married into the other community. The oral testimonies of women, though limited in number, who survived Partition are a testament to the fact that for women there really was no homeland. Even after they were brought back to India, they spent years and sometimes their entire lives in ashrams which were supposed to be their temporary shelter until their families were located and they were returned.

In the female narratives of Partition, there is a silence that surrounds the trauma of having survived the mass migration as well as the violence that was inflicted upon their bodies. While it may be easier to talk about the Holocaust as Jews and Nazis, when it comes to Partition, both the sides are equally guilty. In addition to this, women have found it more difficult to come out and speak about their experiences and lived traumas, and in a way, to deal with and overcome them.

It is estimated that within the next few years, the last survivors of this historical event will have died and with them, so will their stories and their experiences. It, therefore, becomes important for us to ensure that these voices are given a space to be listened to while we still can – as a reminder that the Partition is not just about the division of the land but of its people, of the families that were not related by blood but through culture and humanity, and while we do that, it is also imperative that we acknowledge the mass trauma that an entire generation had to go through instead of writing them off from our history books.