Crimes and their punishments decided by judicial powers have for long been a hot topic for debate not only for criminologists and students of law but for the public in general. The fact that it is not difficult to stir up a debate on the issue of capital punishment proves the aforementioned. However, what demands more conversations around it is the question of whether or not the ‘intention’ with which a certain punishment is administered, is fulfilled.

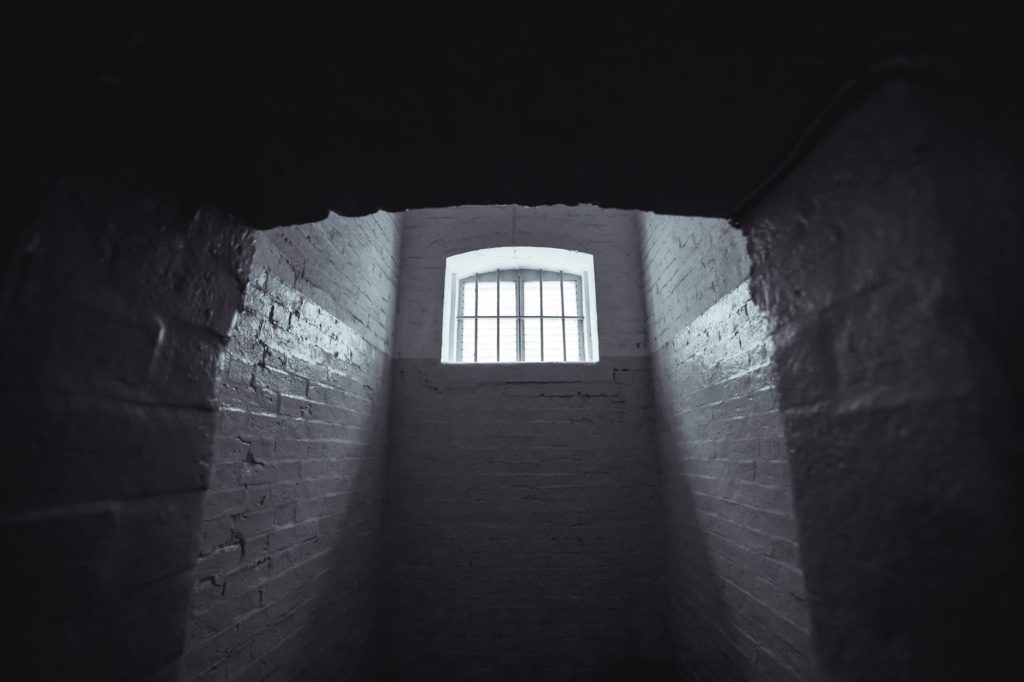

According to World Prison Brief, the percentage of the prison population, including pre-trial detainees and remand prisoners, in India as of December 31st, 2017 is a startling 68.5%. We know that the fundamental objective behind administering prison time on criminals, other than confining them to prevent further crime and establishing a deterrent, is to rehabilitate them; to provide them with an environment wherein they may learn to channelize their energy towards activities that ameliorate their psyche. However, the reality is much too different from what is imagined for these criminals.

To say that incarceration worsens the mental framework of most criminals is an understatement. Though care is taken to prevent clashes among inmates, it isn’t the easiest thing to do seeing as these are indeed the least law-abiding citizens locked together. Therefore having to live in conditions which are fraught and unpredictable insofar that there is no telling when the surroundings get volatile, prisons train the minds of the inmates in a way which is not easy to revamp once they are set free. Similarly, exposure to violence, sexual and physical abuse, witnessing killings and people getting severely injured all gravely scar the minds of the prisoners. Hence, it must come as no surprise that Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) is very prevalent in prison populations.

It has been established for very long now that traumatic events are a major cause of psychiatric illnesses, especially PTSD. Using data gathered from a survey, the researchers at ‘Promises Behavioural Health’ found that being incarcerated nearly doubles the risk that a man will suffer from the devastating condition, which is PTSD. The concern becomes more acute when seen in light of the fact that resources directed towards diagnosing and treating this mass of the population are next to none. It is important to mention here that prison may affect each individual distinctively and chances are that many would even be unchanged and unaffected by their experience of imprisonment. However, we cannot neglect the fact that serving time in prison is no cakewalk; it is a torturous experience, with pain, deprivation and peculiar ways of living and interacting with others making it a fight for survival.

In an interview with Brut India, Jigna Vora shared some details about the time she served in prison. “I totally collapsed mentally, physically,” she says. Recalling the harrowing strip search process she told the reporters how even while she was menstruating she was coerced to strip naked for the process. She also talked about how the food was unhygienic and often contained worms. How are such brutal conditions of living supposed to help inmates transform and become better humans?

When asked to share her insight on the problems with imprisonment in India, Vibha Swaminathan of Lady Shri Ram College for Women said, “I think the main issue is the excessively long wait time for under trial prisoners. Many suffer from inaccessibility to proper legal aid, rendering them stuck in prison for many many years, usually longer than the maximum sentence for the crime they’re under trial for. I think it’s inhumane that vulnerable individuals suffer due to the inefficiency of the judicial system in our country.”

When such an environment is imposed on these criminals for too long, the values learnt under the training of a harsh and disciplined institution like a prison, are internalized. This leads to alterations in individuals in the sense that on the outside they seem to be well-adjusted while are internally brimming with rage, helplessness, alienation, fear and frustration. This eventually renders them incapable of adjusting to the world outside prison, especially when the prisoners are unable to garner social support upon returning. Studies have suggested that PTSD is highly co-morbid with other mental health conditions like substance abuse, depression, suicide, aggression towards community, self-harm, criminality, et cetera.

If sentencing criminals to serve time in prison is yet another form of administering retributive justice, it is safe to say that by scarring the inmates for life our system is doing a wonderful job. However, if the intention is to rehabilitate and recondition these criminals to help them lead more fruitful lives, our current system of incarceration needs to make significant foundational changes.

Writer: Shriya Tandon